The February 1941 Strike brought 300,000 Amsterdammers into the street to protest the first roundup of Jewish people, the only such strike in Western Europe. Every February 25, thousands still gather and lay flowers at the foot of the Dockworker, the statue who symbolizes this mass action. The strikers participated despite the presence of German soldiers and police throughout the city. For the Jewish people, it was a significant moment of affirmation by their fellow citizens.

The Strike challenges progressive Americans. When the word spread that 425 Jewish men had been rounded up and shipped off, the Strike was organized almost overnight. What would it take to bring us into the streets in comparable numbers (almost 40% of the city in that case)? Children in cages? Turning away prospective refugees as the U.S. did in the 1930s when Jews were fleeing Hitler? Slashing food stamps to the bone? The slaughter of school children with assault weapons?

And yet, how much would a strike like Amsterdam’s really accomplish? Although it was a courageous gesture and lifted spirits for a few days, the February Strike sputtered out. The Germans were astonished that the other Dutch would stand up for their Jewish neighbors, so the ensuing crackdown was delayed – but vicious. Only a tiny sliver of people actually resisted from that time forward. Most hunkered down, shook their heads, complied, and tried to survive.

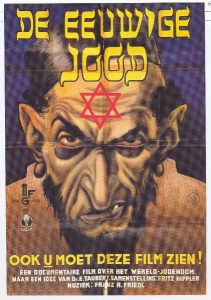

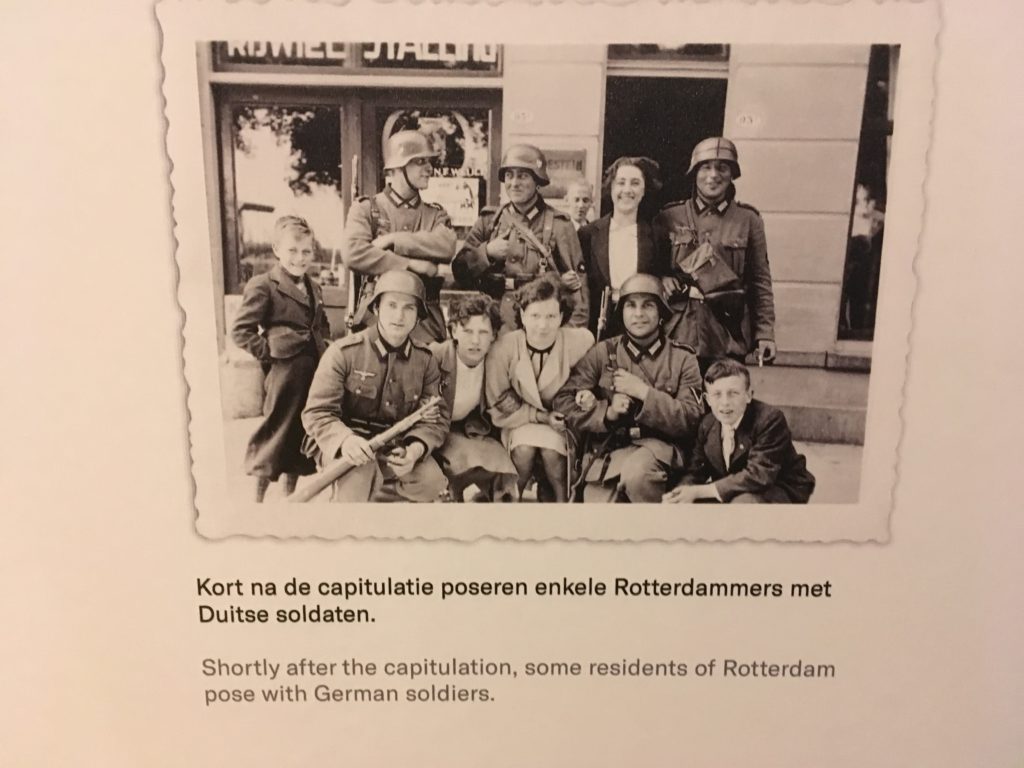

In reflecting on what such people “should” have done, it’s all too easy to make snap judgements and condemn those who were barely surviving on many levels. When the Nazi Occupation began, the Germans carefully started small in attacking the Jewish people and others whom they hated. Initially, the invaders simply turned the other way when local anti-Semites started beating Jewish people up and breaking windows. That set the tone for what was to follow, an air of permissiveness. Slowly but surely, the Nazi propaganda worked. Attacks intensified, depicting Jewish people as barely human, with ugly language to match.

Following the Strike, the other Dutch people were being conditioned not to look, not to notice, much as we are today. The reporting on family separation of refugee families, for example, is a rarity, so that the anguish of children placed with unknown foster families or in institutions is erased. The threats to Vermont’s migrant dairy workers are escalating, but only the workers themselves and close allies hear about it regularly. New prisons are called “detention centers” and are buried in rural areas where legal help is almost non-existent. Our country, 97% immigrants and refugees, is closing the door to asylum seekers. How quickly what is patently wrong becomes normalized.

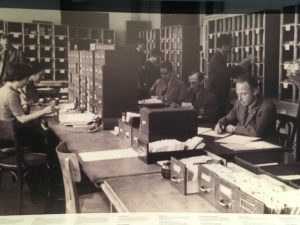

The miracle in the 1940s is that a few Dutch people didn’t buy the Nazi propaganda. Their minds kept working after the Strike, and they resisted wherever they were, however they could. They transcribed illegal BBC broadcasts, they produced and distributed underground newspapers, they hid their Jewish neighbors or strangers, they forged identity cards and more, they cleaned hideaways for airmen, they smuggled Jewish children to the countryside and much more. They risked their lives and their peace of mind, and that of their families. Historians say about 25,000 people resisted, and it could be many more, but it still is far less than 1% of the population.

Most Dutch people believed “It can’t happen here,” and tried to get on with normal life as much as possible. They believed the Germans wouldn’t dare go too far in their anti-Jewish program. The Netherlands had been the safest place in Europe for religious minorities since the Inquisition. Both Dutch Jews and Gentiles believed Hitler wouldn’t dare do in Amsterdam what he did in Berlin. Tragically, 75% of the Jewish people in the Netherlands were rounded up and murdered, 80% in Amsterdam. The Germans made rules about keeping the blinds closed during roundups. Toward the end, they came to the neighborhood of a resister and shot people at random, whether or not they were involved in any way. The poisonous atmosphere daunted people and twisted their thinking. Even when their neighbors were taken away under their noses, they did nothing. Some were the same people who roared into action for the February Strike.

What is happening to us, and what are we going to do about it?

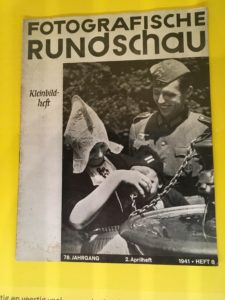

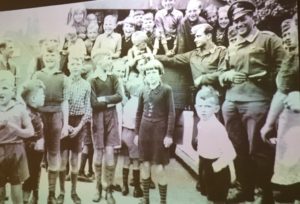

With foreknowledge, it was poignant to see photos of the children of Arnhem gathered as the Germans arrived, with one soldier smiling broadly. How many of those kids would survive one of the bloodiest battles of the war,

With foreknowledge, it was poignant to see photos of the children of Arnhem gathered as the Germans arrived, with one soldier smiling broadly. How many of those kids would survive one of the bloodiest battles of the war,

London’s riches are so numerous that I decided to take the first bus in either direction and see where I ended up. Because my walking is limited right now, I stay off the Tube with its endless corridors and stairways. The bus holds many compensations, however. First, there’s the novelty of the double decker, although for the moment I’m staying downstairs. Then there are the other passengers, mostly older people like me who are often chatty, and mothers with children in buggies who often look exhausted but respond to anyone who plays peek-a-boo with their offspring. In the evening, there’s even a free newspaper to read with the latest bad news about Brexit, the B-word which most of our friends here can’t bear to hear, and no wonder. And that’s in addition to the joys of looking out at the pubs, the houses, the millions of little independent shops, and the gardens.

London’s riches are so numerous that I decided to take the first bus in either direction and see where I ended up. Because my walking is limited right now, I stay off the Tube with its endless corridors and stairways. The bus holds many compensations, however. First, there’s the novelty of the double decker, although for the moment I’m staying downstairs. Then there are the other passengers, mostly older people like me who are often chatty, and mothers with children in buggies who often look exhausted but respond to anyone who plays peek-a-boo with their offspring. In the evening, there’s even a free newspaper to read with the latest bad news about Brexit, the B-word which most of our friends here can’t bear to hear, and no wonder. And that’s in addition to the joys of looking out at the pubs, the houses, the millions of little independent shops, and the gardens. Only yesterday I’d regretted that we didn’t get to see any art on my father’s birthday, despite many other activities which evoked his spirit. A block away was one of the great museums in the whole world, the

Only yesterday I’d regretted that we didn’t get to see any art on my father’s birthday, despite many other activities which evoked his spirit. A block away was one of the great museums in the whole world, the  The grandeur of those old galleries is amazing – the vast height of the ceilings, the number of arches, the gilt here and there, the ornamental woodwork, the silk wallpaper, even the stuffed leather benches and couches (could they be horsehair still?). It feels fresh and cared for, not old and fusty as it easily might. And the paintings! I sat first in a room that was all Venice – Canaletto showing us the splendors of the most special day of the year there, with the Doge’s immense barge ready to be boarded and scads of smaller boats filling the waters; then the more everyday scenes which are in many ways just as beautiful. Soon a delightful baby and her father sat with me, and we had a nice chat about his six-month sojourn here thanks to his wife’s job. I told him about the Thames Walk, and thought what that would be like carrying a baby, and how it might shape their lives. He too traveled by bus, and liked the idea of the bus to anywhere.

The grandeur of those old galleries is amazing – the vast height of the ceilings, the number of arches, the gilt here and there, the ornamental woodwork, the silk wallpaper, even the stuffed leather benches and couches (could they be horsehair still?). It feels fresh and cared for, not old and fusty as it easily might. And the paintings! I sat first in a room that was all Venice – Canaletto showing us the splendors of the most special day of the year there, with the Doge’s immense barge ready to be boarded and scads of smaller boats filling the waters; then the more everyday scenes which are in many ways just as beautiful. Soon a delightful baby and her father sat with me, and we had a nice chat about his six-month sojourn here thanks to his wife’s job. I told him about the Thames Walk, and thought what that would be like carrying a baby, and how it might shape their lives. He too traveled by bus, and liked the idea of the bus to anywhere. Next I ran into Queen Charlotte as rendered by Sir Thomas Lawrence, the German princess who was unfortunate enough to be married to George III, a lovely woman in a wispy gown looking into the distance. No wonder she seems sober, because he had just had his first attack of what was then called insanity. The landscape in the background is of Eton, quintessentially English. I remembered walking across the playing fields there on the Thames Path and seeing the view of Windsor Castle, where this poor lady must have lived.

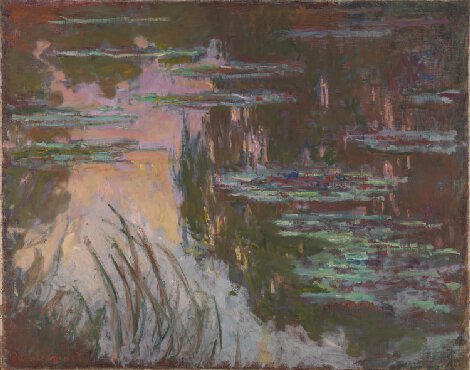

Next I ran into Queen Charlotte as rendered by Sir Thomas Lawrence, the German princess who was unfortunate enough to be married to George III, a lovely woman in a wispy gown looking into the distance. No wonder she seems sober, because he had just had his first attack of what was then called insanity. The landscape in the background is of Eton, quintessentially English. I remembered walking across the playing fields there on the Thames Path and seeing the view of Windsor Castle, where this poor lady must have lived. I jumped ahead to the nineteenth century, and drank in the Turners. Even as a teenager, I loved the swirling mists of color in his paintings, and later began to know enough history to appreciate his depiction of the transitions of his time. How sad to see a great old sailing ship tugged by an impatient steam-powered boat to be broken up in the shipyard for timber! And it had been “The Fighting Temeraire” once upon a time, playing a key role in the Battle of Trafalgar. But that was 1805, and the painting was made in 1839. The ship was towed to Rotherhithe, just a mile or two from Gallery. No wonder history feels so real here.

I jumped ahead to the nineteenth century, and drank in the Turners. Even as a teenager, I loved the swirling mists of color in his paintings, and later began to know enough history to appreciate his depiction of the transitions of his time. How sad to see a great old sailing ship tugged by an impatient steam-powered boat to be broken up in the shipyard for timber! And it had been “The Fighting Temeraire” once upon a time, playing a key role in the Battle of Trafalgar. But that was 1805, and the painting was made in 1839. The ship was towed to Rotherhithe, just a mile or two from Gallery. No wonder history feels so real here. Fortunately for me, a seat opened by a painting I didn’t remember, the spectacular “Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus”, with the Greek hero and his crew sailing away after blinding the cruel giant who ate some of their friends and would have consumed them all. It seems like many paintings in one: the dark mountains and the silhouette of the monster, the gloriously rising sun with the faint traces of Apollo and his chariot bringing the dawn, the splashes of gold on the sea, the incredibly complicated sky with its intimations of blue and clouds of all colors, and the prominent ship with translucent mermaids playing by the prow.

Fortunately for me, a seat opened by a painting I didn’t remember, the spectacular “Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus”, with the Greek hero and his crew sailing away after blinding the cruel giant who ate some of their friends and would have consumed them all. It seems like many paintings in one: the dark mountains and the silhouette of the monster, the gloriously rising sun with the faint traces of Apollo and his chariot bringing the dawn, the splashes of gold on the sea, the incredibly complicated sky with its intimations of blue and clouds of all colors, and the prominent ship with translucent mermaids playing by the prow.

Although the new

Although the new

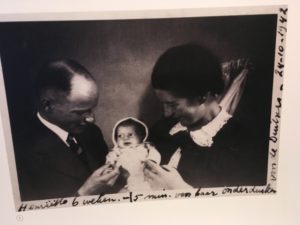

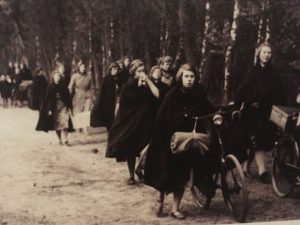

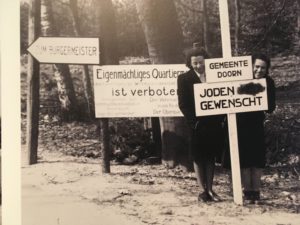

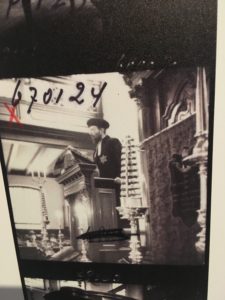

especially Jewish people – had fun and enjoyed themselves even at the worst of times. This photograph of a group of Jewish nurses shows their good humor, even under the Nazi re-named street sign (Jewish Street), and probably after the point where they were only allowed to work with patients who were co-religionists.

especially Jewish people – had fun and enjoyed themselves even at the worst of times. This photograph of a group of Jewish nurses shows their good humor, even under the Nazi re-named street sign (Jewish Street), and probably after the point where they were only allowed to work with patients who were co-religionists.

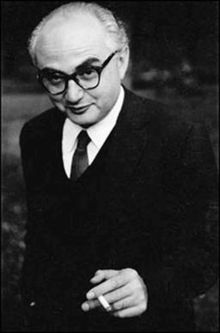

The night before he and a whole group of Jewish people were to be executed, some asked him for words of comfort in that appalling situation. His response as I recall was “These are little people. They can only kill us. They can never destroy what we believe in and what we represent.” They all died as hostages in the dunes at Bloemendaal in 1943. It’s one of anecdotes that stuck with me, and which I cite when people ask me how I could stand so much focus on the grimness of the Holocaust for those 13 years of research and writing.

The night before he and a whole group of Jewish people were to be executed, some asked him for words of comfort in that appalling situation. His response as I recall was “These are little people. They can only kill us. They can never destroy what we believe in and what we represent.” They all died as hostages in the dunes at Bloemendaal in 1943. It’s one of anecdotes that stuck with me, and which I cite when people ask me how I could stand so much focus on the grimness of the Holocaust for those 13 years of research and writing.