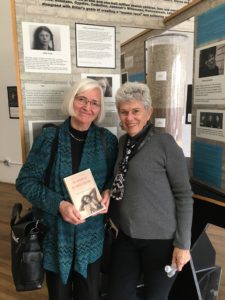

In the 13 years it took to research and write my historical novel An Address in Amsterdam, I could not have imagined the meeting which took place in Philadelphia on Sunday evening, with a man who had been a hidden Jewish child. The setting was a reader’s paradise: the Big Blue Marble Bookstore, a community institution which has shelves to the rafters and loads of activities for everyone in the neighborhood. Just before my event, a group had been making Valentines on the large mezzanine which overlooks the main floor of the store.

Mr. Vega hidden with his “brother” 1944

I’m standing at the top of the steep staircase to greet people as they arrive. An older man comes up first, followed by a woman about his age and a younger couple. When I apologize for the sharp incline, the younger man chuckles and says, “These steps are nothing to the Dutch.” He cocks his head toward the older man, who turns out to be his father-in-law, Lex Vega.

I take Mr. Vega’s warm hand. His eyes are vibrant and liquid, his gaze almost affectionate, his smile glowing and contagious. Because of an illness, he has difficulty speaking, but we are in immediate and real communication even so. The son-in-law continues, “He comes from Ouderkerk, near Amsterdam.”

“Of course!” I say. “The beautiful Sephardic Jewish cemetery is there.” It’s a place I love, and an important scene in my novel took place there.

Mr. Vega’s eyebrows shoot up, and he speaks. His wife and daughter help me understand. “I was born in the house right beside the cemetery, and lived there until I had to go into hiding.”

“But I know the house! I know exactly where you mean.” I could see it, just on the edge of the cemetery grounds. Nearby, the large blue stone gravestones incised with Hebrew letters have stood for centuries.

The son-in-law added, “The family lived openly as Jews well into the war, because his father was the guardian and buried the bodies. But eventually they had to hide.”

Mr. Vega interjected, and this time I thought I understood. “Someone warned you?”

He nodded. Soon Mrs. Vega was by our side, saying she’d read the book. I asked her what she thought of it, and she said, “Of course we know the story.” She paused. “The book was real.”

Even though I had to focus on the reading, I was remembering a spring day, probably in 2002, when I, like my heroine Rachel Klein, needed a break. Day after day, I had been studying how the Nazis carried out their diabolical work in the Netherlands. The horror of it was in my body and mind like a fever, and I had to get away from it. Because I love walking by rivers, I decided to follow the Amstel in the direction of Ouderkerk. Maybe I’d get there, maybe not.

The Jewish Cemetery by Jacob Isaacksz van Ruisdael

My mood lightened as I slipped out of the city, and buildings gave way to freshly mown pastures. Dots of yellow flowers poked up here and there. The river glittered in the surprisingly consistent sun. I stopped for an old cheese sandwich in an ancient café, and paid homage to a gigantic statue of Rembrandt. By late afternoon, I arrived in Ouderkerk, a picturesque village built right up to the water. Wandering along its lanes, I spotted a cemetery with an iron fence around it. The large flat stones seemed to call me in. A sign told me where I was: the Sephardic Jewish cemetery. It took my breath away. No matter where I went, the stories of the Jewish people of Amsterdam would find me. Whatever was guiding me into those stories was gently sending me back to my job. What was that force? Something within me, some long buried truths that needed to emerge? The spirits of the dead, or what the indigenous people call Great Heart? I don’t know how to name that force, but some people call it G-d.

All this came into my mind as I spoke with Mr. Vega. The next day, he sent me his story, able to communicate much more fully by e-mail. It turns out that his parents made no proactive effort to evade deportation. Instead, a woman who worked with the Resistance, Mrs. Catherina Klumper, pushed them to let her hide first Mr. Vega’s grandmother, then himself at age five and his younger sister, and ultimately the rest of the family. Mr. Vega was placed with a loving Catholic couple, first in Arnhem and then in Friesland after the battle of the “bridge too far.”

I could still see the kindness of Theo and Bets van Heukelom in Mr. Vega’s open face. He called them Aunt and Uncle, and enjoyed the company of an older “brother” Theo as well. Unusually, Mr. Vega stayed with the same family throughout the war – and even more unusually, his entire nuclear family survived, and they were reunited. The whole town welcomed them back, and returned all the goods which were in safekeeping. The Vegas were literally the only Jewish family in Ouderkerk, and were liked and respected.

After a few visits following the war and Uncle’s death in 1946, the families lost touch. It always bothered Mr. Vega, and in 2013 his wife persuaded him to make a real effort to find whatever remained of his war family. More than sixty years had passed. Here’s what he writes:

I began to call everybody in the Dutch phonebook with Uncle’s name, “van Heukelom” or Aunt’s family name “Bindels.” Every time, after I had introduced myself, they told me that they did not know what I was talking about. But after fifteen calls, I got Theo on the line. How did I know that it was him? He reacted spontaneously with an immediate answer: “Oh, my little brother in the war!” This was one of the most heart-warming experiences I ever had. Not only had I now rediscovered the family of Uncle and Aunt, but he called me his brother! So it was really true that I belonged to their family!

The once hidden Mr. Vega and his “brother” Theo in 2015

Not only did they reestablish contact, but Mr. Vega went through all the necessary processes to give his Aunt and Uncle the Yad Vashem honor for Righteous Gentiles. The ceremony was held in Ouderkerk last year, and he was able to acknowledge them publicly and say, “I was very well taken care of with affection and with respect for my Jewish identity.” If only it had been that way for every hidden child.

So here’s where Mr. Vega’s story and mine intersected, as we stood at the head of the stairs together. For reasons I’ll never fully understand, it became my task and honor to remember and write about the Jewish people of Amsterdam. His duty was to loop back after decades and to acknowledge the kindness of his war family. And perhaps to let me know that, even though I was born after the war, even though I’m neither Jewish nor Dutch, my book somehow holds some of the stories. Especially of those who will never rest in the beautiful cemetery in Ouderkerk, or any other.

I needed to walk in my own footsteps, too. To remember stumbling sleepily off an overnight bus as an 18 year old to the roar of a megaphone that said “Good morning, Antioch.” I returned to march again and again – to protest the Vietnam war, then to support women’s rights. Then marching wasn’t enough, and I spent ten years in Washington, working first in public interest groups, then for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Federal Women’s Program. I worked for almost everything Donald Trump is attacking. I take it personally. I lived in Washington long before that man did, and I’ll still be marching and supporting good causes there long after he’s gone.

I needed to walk in my own footsteps, too. To remember stumbling sleepily off an overnight bus as an 18 year old to the roar of a megaphone that said “Good morning, Antioch.” I returned to march again and again – to protest the Vietnam war, then to support women’s rights. Then marching wasn’t enough, and I spent ten years in Washington, working first in public interest groups, then for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Federal Women’s Program. I worked for almost everything Donald Trump is attacking. I take it personally. I lived in Washington long before that man did, and I’ll still be marching and supporting good causes there long after he’s gone.

The last few days fulfilled my longtime dreams of what I might do as a writer in the world. Being with two groups in New Mexico to discuss the importance and possibility of resistance gave me a sliver of hope, even ten days before Donald Trump’s inauguration. If there are 35 people in a red state in two locations who are receptive to that message, we need not despair for our country. Around the talks, I got to visit with dear old friends, see countryside utterly different from my usual haunts, appreciate the marvels of sandhill cranes for the first time, and learn from the Pueblo Native Cultural Center in Albuquerque.

The last few days fulfilled my longtime dreams of what I might do as a writer in the world. Being with two groups in New Mexico to discuss the importance and possibility of resistance gave me a sliver of hope, even ten days before Donald Trump’s inauguration. If there are 35 people in a red state in two locations who are receptive to that message, we need not despair for our country. Around the talks, I got to visit with dear old friends, see countryside utterly different from my usual haunts, appreciate the marvels of sandhill cranes for the first time, and learn from the Pueblo Native Cultural Center in Albuquerque.