Although the new Holocaust Museum is in a building which will be extensively renovated, even now it offers the visitor considerable insight. It’s well worth the visit along with the other sites in the Jewish Cultural Quarter. Across the street from the Schouwberg Theater which was the assembly point for deportation, the Museum is located in the school next door to the child care center where the kids were taken care of (a fine institution that did a humane and kind job). The head of the school cooperated with the resistance within the center to save 600 children by smuggling them out. So the building has a distinguished history which adds richness to the Museum site.

Although the new Holocaust Museum is in a building which will be extensively renovated, even now it offers the visitor considerable insight. It’s well worth the visit along with the other sites in the Jewish Cultural Quarter. Across the street from the Schouwberg Theater which was the assembly point for deportation, the Museum is located in the school next door to the child care center where the kids were taken care of (a fine institution that did a humane and kind job). The head of the school cooperated with the resistance within the center to save 600 children by smuggling them out. So the building has a distinguished history which adds richness to the Museum site.

As you enter, a small room to your left beckons, with the stories of a dozen or so of the 17,000 children who were rounded up and murdered. Each has a small case of mementos and photos, and in some cases a supplementary video interview with a person who knew the child. While any of these stories would be more than worth telling, the one that touched me most was that of two cousins, one of whom survived, one not. The survivor, Liesje de Hond , was a three year old who worshipped her seven year old cousin “Deddie.” His actual name was David Zak, but he couldn’t pronounce it. His father was worried that he’d get lost between the two houses on his bicycle, so he had a metal identity card made fro Deddie to wear around his neck. Here they are together.

Liesje was one of the lucky ones who was saved from the day care center. Deddie instead died at Sobibor, and a few years ago archeologists there found his metal identity tag. Although Liesje was invited to visit the camp with a Dutch delegation, they would not allow her to have the tag, or even to hold it for a moment. Instead, she has a replica which is on loan to the Museum – all that is left of her beloved cousin. “I think about it every day, a lot. I still miss him.”

In addition to the individual stories like these, the faces of more than 4,000 children appear in an ongoing slide show. Some are shining portraits like the above which make you cringe, while others are blurry images that are harder to relate to.

Even with all I know, it’s hard to take in the fact that each one of these children was deliberately murdered, taking away a whole world when they died. Just across the hall is a room with a huge wall covered with names from the Jewish Digital Monument, which are constantly changing. The encouraging part is that, in one corner, a box indicates “researcher looking for (name) from the Netherlands,” or Australia, or the U.S. or wherever. It does show that these 104,000 people who were murdered are not forgotten. They are still being looked for all these years later.

In the Museum courtyard where the children at the school must have played, three timelines are shown, one above the other: events in Europe, in the Netherlands, and right there in the neighborhood. Illustrated with photographs, the chronology helps make the connections – beginning with persecution in Germany and the influx into the Netherlands, and finishing with the Holocaust itself. The signature exhibit, The Persecution of the Jews in Photographs, is in a large gallery across the courtyard. Taken together, they are an accessible education for anyone who isn’t familiar with the Holocaust in the Netherlands and how it was carried out. Having studied the photos of this period in so many times and places, I was familiar with many of the images, but some gave new insight. For example, the curators collected all the recordings of the first roundup in the J.D. Meijerplain, a scene which I reconstructed in An Address in Amsterdam. But one of the few photos I’d never seen gave a new and dynamic sense of the brutality of that moment.

The way the men are almost crawling, the two soldiers hovering over them, the rifle butt and its proximity to the head of one man – you can almost smell the terrible danger. Or smoke that is to come. The calamity of it all came back to me again, full force. I was reminded that 427 men were rounded up that first day, sent to a Dutch camp (after being held at what is now the Lloyd Hotel), and then on to Mauthausen. Only two survived the war.

As I researched An Address in Amsterdam, one of the big surprises was that people – even and  especially Jewish people – had fun and enjoyed themselves even at the worst of times. This photograph of a group of Jewish nurses shows their good humor, even under the Nazi re-named street sign (Jewish Street), and probably after the point where they were only allowed to work with patients who were co-religionists.

especially Jewish people – had fun and enjoyed themselves even at the worst of times. This photograph of a group of Jewish nurses shows their good humor, even under the Nazi re-named street sign (Jewish Street), and probably after the point where they were only allowed to work with patients who were co-religionists.

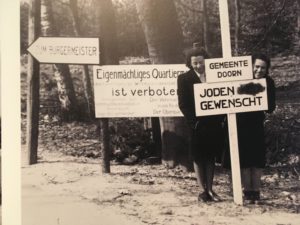

Similarly, these two naughty young women have blacked out the “not” in a “Jews not wanted” sign:

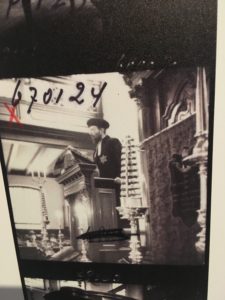

For the first time, I saw an image of someone I have admired ever since I read about him, Rabbi Philip Frank.  The night before he and a whole group of Jewish people were to be executed, some asked him for words of comfort in that appalling situation. His response as I recall was “These are little people. They can only kill us. They can never destroy what we believe in and what we represent.” They all died as hostages in the dunes at Bloemendaal in 1943. It’s one of anecdotes that stuck with me, and which I cite when people ask me how I could stand so much focus on the grimness of the Holocaust for those 13 years of research and writing.

The night before he and a whole group of Jewish people were to be executed, some asked him for words of comfort in that appalling situation. His response as I recall was “These are little people. They can only kill us. They can never destroy what we believe in and what we represent.” They all died as hostages in the dunes at Bloemendaal in 1943. It’s one of anecdotes that stuck with me, and which I cite when people ask me how I could stand so much focus on the grimness of the Holocaust for those 13 years of research and writing.

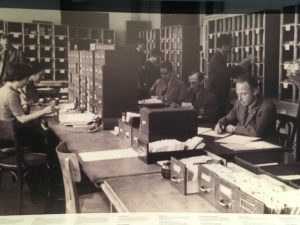

On the other hand, I was chilled by the Museum’s photograph of the Card Catalogue of the Jewish Council, which was used to make the roundups possible. The employees we see in this photograph were almost surely murdered after May 1943 when the Germans revoked the exemptions from deportation for 7,000 of the Council’s 14,000 exemptions. One of the scenes that was purged from An Address in the effort to make the length more manageable was Rachel’s encounter with a former neighbor who has gone to work for the Council in this very department. In the scene I wrote, she’s become a supervisor, has a brand new suit and looks and sounds better than ever. She even encourages Rachel to apply for a job so she’d be safer. This photograph shows what would have been her workplace.

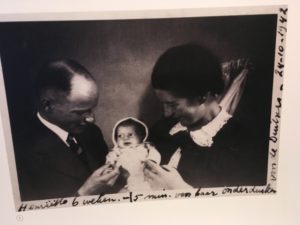

This photograph of six week old Henriette van der Hal a few minutes before she was taken into hiding separately from her parents has a far, far happier ending than most. They were actually reunited after the war (although many such reunions were far from smooth, especially when an infant had formed a bond with the host family and vice versa.)

In terms of my own work, the following photograph is the one which will push me the hardest. It shows two cups of tea on the nearby windowsill, as if you and I had just finished drinking it together. Below us is a group of our Jewish neighbors from the Lekstraat in Amsterdam who have been forced out of their homes, and are about to be deported. Other Gentile people like us are sitting in their window opposite, just watching, as we are just watching. If I were writing another book, this could be the cover.’

In a separate space in the Museum basement, you’ll find a project in honor of the 80th anniversary of Amsterdam’s First Montessori School which was instituted by Dutch American artist Willem Volkersz in 2016. He wanted to commemorate the lives of the 182 graduates who did not survive the war, 179 of whom were Jewish and three of whom were resistance workers. The result is a wooden suitcase for each person, with their name, birth year, and death year and place. When the suitcases arrived in Amsterdam, they went to the school, not the museum, and current students took responsibility for walking them to their new home together. When they arrived, the students decided how to stack and order the suitcases around a neon sculpture of a single person which is also part of the exhibit. Now, other schools are invited to come and do the same, and to research the individuals using the Digital Monument. It’s a simple idea but it was affecting to experience it, especially the film of the kids walking the suitcases by the Dockworker.

Overall, the Museum is full of interest and insight, and it does find the balance between the horrifying and the inspiring – or perhaps more accurately, it throws a lot of both at you, and somehow you have to make your peace with it. It will be fascinating to see how they develop the space into more exhibits.

During my 13 years researching and writing

During my 13 years researching and writing