On this Holocaust Remembrance Day, I think of the hundreds of people of all ages whose photos I saw in the temporary National Holocaust Museum in Amsterdam (under development now). Here is a group of them celebrating Passover in hiding in Zwolle, which in itself was a form of resistance.

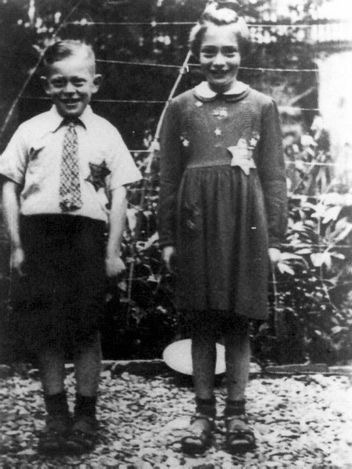

Some Dutch Jewish people lived through the war, but most – statistically 80% in Amsterdam, or 75% in the Netherlands as a whole — were mass murdered.

Only when I was in my fifties did I realize that many of them were rounded up in July 1942, the month when my parents were married in the small farming town of Sussex, New Brunswick on a sunny afternoon. The month that was so happy for my parents was among the worst for Jewish Amsterdam. The deportations were at their height. The trams were commandeered on six July nights between midnight and 2:00 or 3:00 a.m., operated by the regular crew (who were excused from curfew on these nights only).

Photographer: Charles Bönnekamp, Member of the Resistance.

Their job was to deliver Jewish people to Centraal Station so they could be transported to the Westerbork Transit Camp, and on to what many still believed were “work camps” from there. On only three nights, 962 people were sent to Westerbork – fewer than the Germans had demanded because the Jewish Council struck some lucky names off the list, and others failed to report. On July 31, SS-ObergruppenführerHanns Rauter reported with satisfaction that the transports had all gone “smoothly” and that no future difficulties were foreseen.

According to Jacob Presser in Ashes in the Wind, daytime was also dangerous, especially that fall of 1942: It “was best for getting hold of the most defenseless – sick people, invalids and children, and quite particularly children in orphanages. Old men and old women would henceforth be seen roaming the streets, afraid to stay at home. They strayed about, sitting on steps (park-benches were forbidden to them), trying to find out what was going on, and asking odd passers-by if everything was quiet their way. Then they would shuffle on, sooner or later to fall into the hands of their persecutors.”

Just as my parents’ happiness coincided with this immeasurable loss, today many of us continue our relatively comfortable lives while so many are in agonizing peril. The contrasts are dizzying. This photo was taken at the Ukrainian Embassy in Washington in March, where I went to lay flowers. Just a gesture, along with donations of course, yet it still felt important.

Ukraine is the crisis most in the headlines, but we still have tens of thousands of asylum seekers in limbo in Mexico, with almost 10,000 documented cases of rape, torture and other abuse there since January 2021 alone. Millions in Africa are on the verge of starvation, many of them children. How do we live with these incongruities?

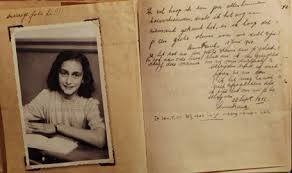

One part of our duty to the ghosts of the Holocaust is surely resistance to what we know is wrong – whether that is human rights violations, environmental degradation, or the erosion of democratic rights. In their honor, however, we must also celebrate life. I remember how shocked I was when a photo of a Jewish couple marrying in Amsterdam under the Nazi occupation, wearing the hated stars but otherwise decked out for their wedding day. Even under the Nazis, the couple found beauty and connection, and continued to celebrate it.

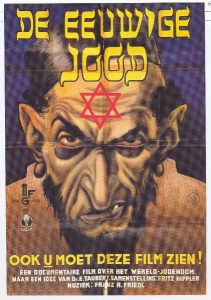

Many Jewish people and others kept on being generous even under the Nazis and tried to help people, both by resisting and otherwise. Dare we do less? In addition to remembering those who died in the Holocaust, Remembrance Day is a time to interrogate ourselves now.

Another part of the duty of remembrance beyond resistance is to build a world where we do not replicate the conditions which led to the Holocaust. If there were ever a time to instill in children the value of every single human life, it is now, with the right wing in the ascendant worldwide and human rights abuses commoner than ever. In addition, while today’s youth will have new resources at their command, unless they learn to love the earth enough to curb human greed, they and the planet are lost.

The time honored creations of humanity – our books, paintings, building tools – must be put into their hands. They need to know what we humans, including them, are capable of, in both the best and worst sense.

When we speak about the Holocaust, let’s not stop with the death camps. Let’s talk about what the people who were rounded up and murdered loved in life, what they created. The beautiful meals (shabbat or otherwise), the weddings and births. When we talk about Jewish Amsterdam, let’s speak of the synagogues they constructed, both the grand and the modest. Let’s remember the diamonds they cut and the union they organized, their creations in every aspect of the city’s life, the pots and pans they sold, the people they healed as doctors and nurses. Let’s talk about the humor of the patent medicine salesmen, the cabaret with its catchy tunes and mordant satire even at Westerbork, the elegant hotels they built.

Amstel Hotel, Amsterdam

Their deaths sit in our hearts, immutable, ever murmuring and reminding us of their and our sorrow. May those murmurs move us to act for peace and freedom in our own beleaguered time.

And may we remember not just their gruesome deaths, but their human lives and achievements.

During my 13 years researching and writing

During my 13 years researching and writing