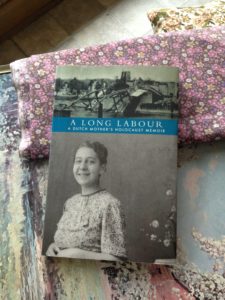

Rhodea Shandler’s A Long Labor: A Dutch Mother’s Holocaust Memoir is a treasure.

A Dutch Mother’s Holocaust Memoir

When I first began to learn about the Holocaust and resistance in the Netherlands, I expected the stories to be grisly and the heroes to be larger than life. Very few stories have a happy ending in that time, and even those that do involve loss, terror and many shades of grey. And yet. There’s inspiration to be gleaned by seeing that ordinary people acted with courage, and that they were human, too, sometimes failing to do what they knew they should.

Rhodea Shandler faced many of the same dilemmas as the fictional characters in my historical novel, An Address in Amsterdam, about a young Jewish woman who risks her life in the Resistance. Rhodea gets pregnant while in hiding on a farm, and the formerly welcoming hosts freeze her out emotionally and practically (less food under worse conditions). Only because another Jewish woman in hiding with the same family is a nurse does she successfully deliver her baby in breech position, of course with no anesthetic or proper sanitation. Similarly, when my novel opens, my heroine Rachel is making a delivery to a wardrobe full of hidden Jewish people in a basement. They all crush in together as the police raid the house. Rachel feels another woman’s rounded tummy mashed against hers, and wordlessly learns that she’s pregnant, and of course it must be a secret. The hazards of the noise of childbirth, much less a baby itself, were more than most hosts could take on – especially given that they were already risking deportation, execution, imprisonment and/or torture.

Like many Jewish people who survived the Holocaust, Rhodea did not feel compelled to record her story until very late in life, and in fact died in 2006 just before this book was published. She takes us through the warning phase before the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands, when the small NSB (Dutch Nazi Party) was still being seen as innocuous:

“Since Holland was a democracy, the NSB had the right to try to influence the people by means of rallies, hate mail, newspaper articles and so on. Initially, most Dutch people just made jokes about them. It was such a small party that it did not seem strong enough to make trouble. We knew they were there, but we thought they were ineffectual. . . What could we possibly have to fear?” Page 52

In fact, it was the NSB and their followers who beat up on the Jewish community after the Nazis invaded, far more than the German soldiers. They were under strict orders to behave properly toward their Aryan brothers – a situation which changed radically after many Dutch made it clear that they regarded the Germans as oppressors.

Although Rhodea was never in the resistance, her perspective fascinates me as that of a young Jewish woman, and one who survived the war in hiding. Her story is different from the Amsterdam situation with which I am more familiar, because she lived in the small northern city of Leeuwarden, where the Jewish population was virtually exterminated. Although she moved several times from one hiding place to another, Rhodea was not betrayed by her hosts, only treated badly when she was pregnant. She herself understands why her situation terrified them. Again and again, she shows what a big heart and compassionate perspective she has.

However, a moment arrives when she does something that haunts her forever. She was working with mental patients at the Jewish asylum at Apeldoorn, where the staff had advance warning to get out. Her husband spoke to her by telephone and insisted that she leave immediately. After helping some of the patients prepare to evacuate, Rhodea decides that it is time to save herself, even though other staff are remaining. She takes off her Jewish star, dresses in street clothes, and leaves her identification behind. Her colleagues are angry:

“They looked at me as a traitor; they were so dedicated to their work. . . I probably would have stayed too if my husband hadn’t been so adamant on the phone that I come home. I knew I had to look after myself first. It had really come to that point.” page 80

Her agony is compounded when she encounters some of the patients already wandering around the town as she heads for the train station. They of course recognize her as she shoos them away, an action which haunts her for years. “Was I a deserter?” she asks herself, even knowing that staff and patients were all seized and deported a few hours after she left. There were no survivors.

I’d read about the horrors of persecuting and exterminating the residents of this asylum and their caregivers, although this is the first time I’ve read a first person account. The situation appears in my novel because my heroine’s father is a physician who had recently admitted a patient there. When he hears of the Nazi raid,

His conscience was wracked by the thought of all those unstable people being subjected to even more terror. “Just before we came here, I had a man who attempted suicide admitted there. He was a peddler who couldn’t support his family anymore because of the Nazis.” He shook his head, looking like an old man who doesn’t understand the world anymore.

Like Rhodea, An Address’s heroine, Rachel Klein, comes to the point where she must save herself and her family – but by then she has done months of work for the underground. She is tired and terrified, and something happens which is a last straw for her. Even knowing that she had to do what she did, both the real Rhodea and the fictional Rachel are haunted by saving themselves, a particular kind of survivor guilt. They also respond to their persecution and predicament as Anne Frank did, by becoming more broad-minded and humanitarian. Rhodea puts it beautifully:

“Even now, the knowledge that all our loved ones, friends, family and everyone who suffered in concentration camps and jails did not survive their ordeal makes me jump out of bed in the middle of the night with tears running down my cheeks. although it was 60 years ago that all this happened, even now it is unclear to me why the Jews were so hated and even nowadays continue to be persecuted in certain groups.

“It causes me to try to be benevolent and understanding, and to avoid confrontation or judgment of others who are different from me. This is the only light that I see now.”

For more information about the book, click here.