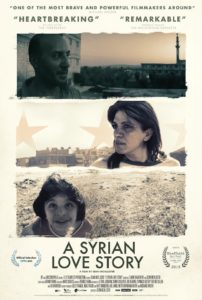

As someone who is always fascinated by women in the resistance, I was curious about Raghda Hassan, the revolutionary heroine in Sean McAllister’s award- winning documentary, “A Syrian Love Story.” Every fall, the Vermont International Film Festival shows social action films which bring the world to our doorstep. I wondered how Raghda would compare to Rachel, the fictional heroine of An Address in Amsterdam who joins the underground against the Nazis. The film is the heartbreaking chronicle of the oppression of the Syrian people, and the dissolution of the marriage, as well as the calamity of the family having to leave first their neighborhood, then their city and country.

Early in the film, Raghda’s Palestinian then-husband, Amer Daoud says, “She’s a very strong woman, and I am a very weak man.” At that point, she was in prison, but she is eventually reunited with her husband and sons. Even to the naked eye she is deeply traumatized both physically and otherwise. The film focuses more on Amer, in part because his English is better. We never learn enough about Raghda and why she made the decisions she made.

I found myself impatient with filmmaker McAllister at times despite his laudable commitment to this film. He says that he had the same experience as Raghda when he was picked up and jailed by Assad’s security forces. By definition, a man is not subject to the same torture as a woman, and no British citizen with an embassy and press corps behind him is in the same position as a Syrian – particularly a known revolutionary. Moreover, because of the film in his captured camera, Raghda and her family had to flee their country for Lebanon.

In the end, Amer and the children are settled in France, but Raghda is in Turkey working in a high position as an advisor to the Syrian opposition government. For the first time, we see her as she must have been before she went to prison, with the composed face of someone doing what she truly wants. She has lost her husband and children but is glad that they are safe. She’s been tortured, moved endlessly, been forced to live away from the home she passionately loves. She has seen Assad triumph again and again, slaughtering his own people.

Raghda smiles. “I still have hope for humanity and freedom and my country.” She is a heroine in the old fashioned sense. Rachel is just as brave when she faces soldiers and police on the street, with illegal documents in her pocket. But she does reach a breaking point, where saving herself and her family becomes paramount. She is not a flame that will burn itself out to the limit like Raghda. She’s an ordinary teenager who turns into an activist and does the right thing – not the one in a million superwoman who is Raghda. I admire her greatly, but she wasn’t my subject.

I pray that Raghda has enough notoriety through this film to protect her, and that her faith has not been utterly destroyed by the continued massacre in Syria.