Kristallnacht is significant because it was a moment of warning about what was to come. What appeared to be individual violence carried out by thugs was specifically sanctioned and incited by the state. What happened that night of November 9-10, 1938? As always, there was an excuse.

Thousands of Polish Jews had been expelled from Germany, and an enraged Jewish teenager shot a German diplomat as a result. The diplomat died about the same time as a big Nazi celebration, and Goebbels used the occasion to call for a rampage – but not officially. “The Führer has decided that … demonstrations should not be prepared or organized by the Party, but insofar as they erupt spontaneously, they are not to be hampered.” This was both a call and a license to vandalize Jewish homes, businesses, and synagogues. The word was passed down from party officials and the Security Police to their local outlets. Although the Nazis later tried to maintain the fiction that these events happened locally, it’s clear that they were orchestrated from Berlin.

The numbers tell one part of the story of the night of November 9-10: 91 people dead, 267 synagogues desecrated or destroyed, some of them burning through the night in full view of fire departments which were ordered to watch unless nearby buildings were threatened. More than 7500 Jewish businesses were destroyed and looted. But that’s only part of the story.

Kristallnacht was the moment when the German state first arrested people only because they were Jewish. They took 30,000 Jewish men, mostly young and vigorous per the orders from above, shipped them off to work and concentration camps. (The men below were marched through the streets and forced to watch as a synagogue burned.) Some died of the camp conditions, but many were released when they agreed to immigrate.

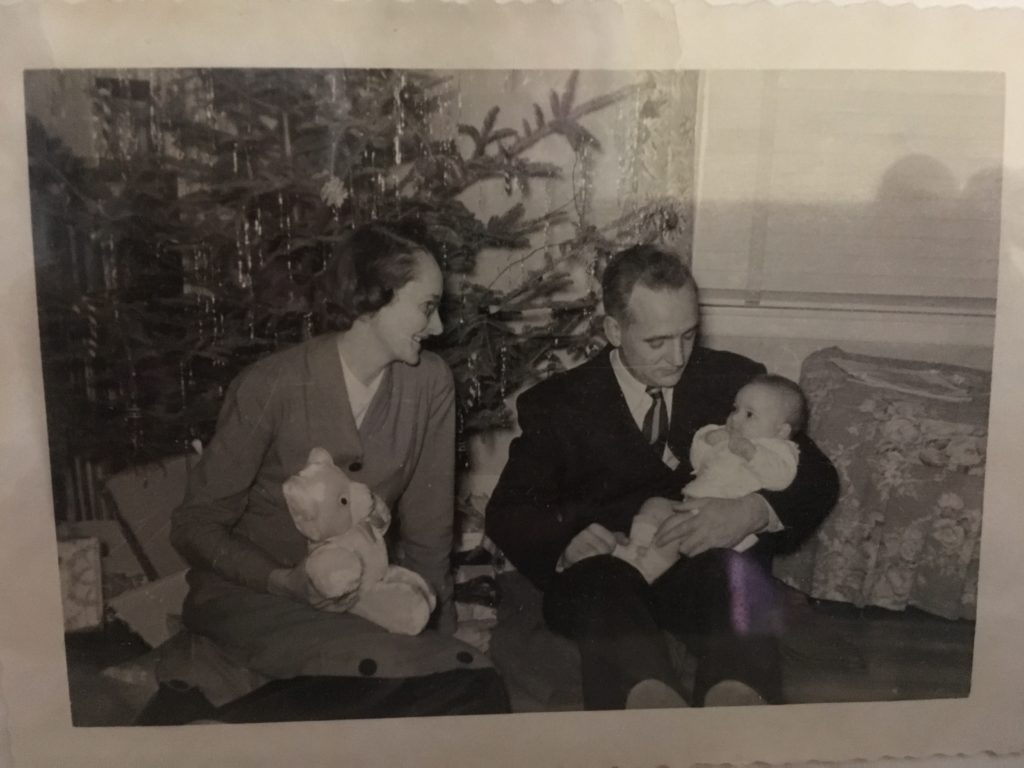

That’s where Kristallnacht and my own life’s work intersect. Kristallnacht sounded a warning that German Jews could not ignore. The Netherlands had been neutral in World War I, and there was a longstanding, well integrated Jewish community there. After Kristallnacht, it’s not surprising that more than 40,000 German Jews applied for a visa to enter the Netherlands, but only 7,000 got one, and even they were put in camps. In desperation, 2,000 more refugees snuck in, and at least the Dutch didn’t send them back, although they did incarcerate them. Is this an echo of the situation of refugees who try to enter the U.S. today? We’ll come back to that point.

Unfortunately, most of the German Jews who made it into the Netherlands were rounded up and murdered. Volumes have been written about how and why the Holocaust could have happened in as open and tolerant a society as the Netherlands. One factor was surely the superior systems the Dutch developed to identify who lived where, in an orderly population register which made it easy to check whether an identity card was genuine or not. It also greatly facilitated roundups by showing where the Jewish people were living. The Holocaust was also facilitated by the fact that the Dutch were and are traditionally a law-abiding people who basically trusted their government. There was no tradition of resistance there, as there was in countries like Belgium, France and Italy. Many other factors have been explored in response to the question, “How could the Holocaust happen in the Netherlands – and to such a devastating degree?”

Whatever scholars may differ about, the collusion of ordinary people was an absolutely key factor. Many minded their own business and tried to keep life going on as normally as they could, activities which would have been benign in a different time, but in this time made them colluders with the Nazis.

Looking at the situation instead from the Dutch Jewish point of view, it seems strange that most of them simply did not believe that they would lose their homes, their businesses and professions, their freedom of movement and ultimately their lives. We cannot underestimate how safe they felt. Let’s hear from Dr. Jacob Presser on this point. Dr. Presser was a Jewish historian who himself survived the war by hiding, and he spent 12 years researching and writing the classic volume Ashes in the Wind: The Destruction of Dutch Jewry. Here’s how he depicts the mood of his Jewish countrymen at the beginning of 1942:

“Many pinned their hopes on the likelihood of Germany eventually losing the war, and consoled themselves with the knowledge that, however bad their position, it could have been much worse. Moreover, few Jews believed that the Germans would carry their policy to the limit. True, there had been raids and hundreds had died, but, thank God, most Dutch Jews had been allowed to remain in their old homes. True also, the Germans had sounded the ugly word of ’emigration,’ but had they not prefixed the comforting adjective ‘voluntary’ – and was the measure not directed at foreign rather than Dutch Jews?” That gives us a sense of why only about one Jewish person in seven hid.

We’ve all heard of the Dutch resistance and revered it. Having studied it for 13 years as I researched and wrote An Address in Amsterdam, I honor what those people did, in fear of their lives – especially those who had the double jeopardy of being Jewish. That’s why I chose to write about a young Jewish woman who joins the resistance. But as much as we honor those resisters, we can never forget how few they were. Yes, historians say 24-25,000, and I think we can double that safely if we include people who only helped occasionally. But even so, we aren’t up to ONE PERCENT in a country of 8.7 million.

No one can review this history without a sense of apprehension. Yet there are so many differences between our situation now, and that in Germany or the Netherlands under the Nazis.

- We live in a constitutional democracy

- Our press is still speaking up to some extent

- Violence against persecuted groups is still sporadic and occasional, and

- We do have elections so we can correct the course.

And yet – who among us has not wondered

- Are we sliding down the slope from civilization to barbarism? Because it is a slope, not a single moment of choice.

- Is the American Jewish community not, like those in Germany and the Netherlands, deeply integrated into society at large? Yet the fact of assimilation did not protect them.

If we look back to the times that began with Kristallnacht for inspiration as well as horror, what can we find to guide us now? Kristallnacht was a time when many people woke up and realized that the Nazis were in earnest, that their hatred had turned to broken bones and windows, desecrated synagogues and 30,000 Jewish prisoners. Some of those people who woke up resisted, by fleeing or becoming active against the Nazis or both.

Can we make this anniversary of Kristallnacht our own moment of awakening?

When we hear code words for white nationalism and supremacy become acceptable in public discourse, can we speak up against them?

When we hear of hate crimes – whether they are in Charlottesville or Sacramento or Omaha – whether they are against peaceful protestors or African American men or someone who looked Muslim — can we respond with empathy and unity, as we did for Pittsburgh.

Can we say that whatever acts of hatred the U.S. government itself is committing must be stopped – and by us? To take a single example, think of children who are refugees and immigrants like my impoverished ancestors and perhaps yours. They are being stolen from their parents, just as they were at the gates of other camps. Can we claim those children, imprisoned in “tent cities,” that barbarous euphemism? Can we fight for them as strenuously as we would for our own children? Are they ours? If our tax dollars are paying for them to be kidnapped and imprisoned, are they not ours?

Let’s change gears and focus for a moment on the people who stayed home for Kristallnacht. They may have been quieter anti-Semites, or they may have been friendly to the Jewish people and disgusted by the violence in the streets. But they didn’t stop it. This is the story in the Netherlands, as well.

I wish I could offer you more words of comfort today. But all I can bring you is what your people have always done – to continue your hard work in the service of other persecuted people and yourselves. Work that everyone is morally and ethically required to do, whether or not we ever see the results. We are in a time when that spirit is more needed than ever.

Let’s not allow the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht and the murders in Pittsburgh to terrify and dishearten us. May they instead awaken us to be even more active on behalf of justice, and what used to be called “the human family.” As I need not remind you, “You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.”

Untitled, by Barbara Chen

This talk was part of the Shabbat service at the Israel Congregation of Manchester, Vermont, on Friday, November 9, 2018. Many thanks to them for inviting me.

The last few days fulfilled my longtime dreams of what I might do as a writer in the world. Being with two groups in New Mexico to discuss the importance and possibility of resistance gave me a sliver of hope, even ten days before Donald Trump’s inauguration. If there are 35 people in a red state in two locations who are receptive to that message, we need not despair for our country. Around the talks, I got to visit with dear old friends, see countryside utterly different from my usual haunts, appreciate the marvels of sandhill cranes for the first time, and learn from the Pueblo Native Cultural Center in Albuquerque.

The last few days fulfilled my longtime dreams of what I might do as a writer in the world. Being with two groups in New Mexico to discuss the importance and possibility of resistance gave me a sliver of hope, even ten days before Donald Trump’s inauguration. If there are 35 people in a red state in two locations who are receptive to that message, we need not despair for our country. Around the talks, I got to visit with dear old friends, see countryside utterly different from my usual haunts, appreciate the marvels of sandhill cranes for the first time, and learn from the Pueblo Native Cultural Center in Albuquerque.