For the last several weeks, I’ve been asking myself what people in Amsterdam 1940-45 would say to us now, in the time of coronavirus. Yesterday, the New York Times published “The Lost Diaries of War,” with the subtitle “Volunteers are helping forgotten Dutch diarists of WWII to speak at last. Their voices, filled with anxiety, isolation and uncertainty, resonate powerfully today.” So the ghosts are speaking directly to us. It was so synchronistic that I wanted to share my thoughts with you immediately.

Even though An Address in Amsterdam was published more than three years ago, and I finished writing it a year before that, its characters still speak to me every day. For the first few years, they pushed me to be even more of an activist, to speak out about the perils of our times. More than anything, they told me, “Act now, before it’s too late. In this time of plague, I’ve again been looking to those ghosts for guidance. The resisters would probably counsel us to watch out for sleight of hand by those in power, to be aware of what they can do with one hand while our eyes are on the other. I think particularly of the suspension of environmental regulations and laws.

Learning from the People who Hid

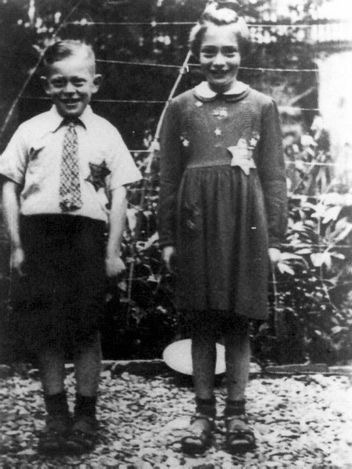

But it’s not just the resisters who have something to offer us now. When I first began learning about 1940-45 in Amsterdam, I was shocked by a photo of bathing beauties stretched out langorously on lounge chairs – while in hiding from the Nazis. They were smiling and laughing, fashionably exposing their perhaps too thin figures. How could they possibly be enjoying themselves, I wondered; but they clearly were. Another picture showed two little kids, Jansje and Benjamin Pais, grinning and wearing their best clothes, perhaps for the first day of school. Someone had sewn the Stars of David on, not pinned them which was prohibited. (Jewish people were actually charged for the stars, so this increased the profits.)

The mystery of how these people could be happy in their appalling circumstances compelled me to dig more deeply into their collective stories. The more I learned, the more grateful I was for the many privileges of my own place and time – my access to food, my freedom of movement, my ability to be in touch with people I love.

In the time of coronavirus, I am again learning from them: to taste the sweets of the moment, whatever they may be. To be sure love flows out of me and my house every day. To notice every individual crocus and daffodil that breaks the soil in our garden, and everyone else’s. To let no small desire on my partner’s part – for raisins, for calm, for Chopin – go unfulfilled. To remember the people in detention and prison who are so much worse off than I am, and try to help them. To wash our hands as a sacrament, the way the Muslims do five times a day before their prayers. With the children in my life, I try to remember that this is their childhood, right now. It can never be replaced or deferred. They must play and have all the joy they can. Human creativity being what it is, they will find ways to make stories and sense even of the plague. They are wondrous beings who can pull us adults into the moment.

Beyond Survival

I’m sure the bathing beauties tried to keep each other’s spirits up, using whatever materials were at hand. If anyone faltered in security precautions or broke down, everyone would suffer or worse. For us in our much easier situation, our first duty is maintaining our good health and good humor. After reading many accounts of these circumstances as I researched An Address in Amsterdam, I did my best to re-create the life of the fictional Klein family in hiding. They, and the real people whom they represent, had to occupy themselves in a way that upheld their sanity and their health. Surviving until a better day was their first priority. How did they live with the fear? Not by saturating themselves with information, which was only available through their hosts.

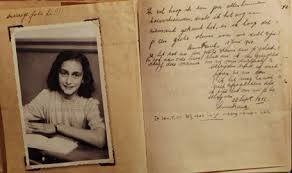

All they could usually do to make themselves safer was stay quiet, so they distracted themselves. People who could read, read. The artists drew, and musicians found ingenious ways to practice (like Rose Klein with her piano keyboard handmade of paper). They played endless games. Some, like Anne Frank or the diarists the Times reports on, found solace in writing.

People had conversations which probably would never have happened in normal circumstances. And they dealt with endless moments of terror when someone stepped the wrong way on a floorboard. Writing the part of An Address in Amsterdam when Rachel and her family are hidden was even scarier than writing the earlier chapters when she was on the street facing the Nazis.

The ghosts were living with far worse fear than we are, and a situation that seemed endless. Every action we take these days is a kind of Russian roulette, especially in my age group. But I find that the same things that helped the ghosts in their far more difficult predicament help me: love, a belief in justice, an appreciation of beauty, and the sense of being connected to others. Even years after I first met them in Amsterdam, the ghosts are still guiding me.