Launch at Phoenix Books Burlington

Words I never thought I’d hear: a call from Phoenix Books to say “Your book launch is sold out. We can do standing room, but the 100 seats are sold.” Not to mention “Your makeup person stopped by to wish you luck.” I never had a makeup person before. But I’d been working toward this night for 13 years, and I didn’t want the video to look amateurish. As I slipped on my carefully chosen ivory silk shirt (over the most expensive bra I’d ever bought) and the mauve velvet jacket, I wondered if I could get through the evening without losing my voice to tears. It had been a long haul.

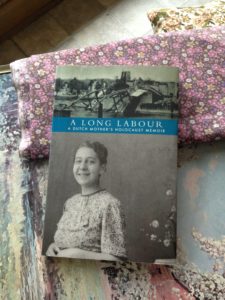

As the friend who introduced me said, An Address in Amsterdam wasn’t a book that wrote itself. Apart from facing the pain of the Holocaust and resistance in the Netherlands, an enormous amount of research was needed, first to understand the backdrop of the story, then to ensure that the plot and characters were realistic to the time, then to refine the details. For example, what people ate was determined by supply, and by their access to ration coupons and the black market. Even something as simple as a walk in the park was complicated for Jewish characters, who were banned from public spaces after a certain point.

When people started to arrive for the launch, my longtime partner and greatest supporter, Joanna, greeted them with an orange rose for the women (the Dutch color) and a white carnation for the men (the flower of resistance). They descended the long open staircase to find me at the bottom, grinning so hard that my face ached. Hug after hug followed. All kinds of people came: my old friend from Washington in the seventies, my faithful writing group, the mother of our fairy goddaughter, the indispensable editor from Our Bodies Ourselves, my hairdresser and her daughter, my full moon circle, colleagues, clients and former clients, neighbors, and most of all our friends from every walk of life.

Everything was in place and ready to be recorded by the first-class videographer Kenric Kite, who had worked with me before on “Anne Frank’s Neighbors: What Did They Do?” and the brilliant photographer Karen Pike, who had done the author photograph I love. Two stunning bouquets were on either side of the podium and book display: bells of Ireland, snapdragons, lilies, delphinium, all in resplendent corals and golds and azure and green. The room was abuzz, almost like a flock of birds on the lake during migration, everyone in communication. Looking out over the crowd, I couldn’t believe what I saw: chairs all the way to the edges of the room, with every visible seat filled except a few places in the front row, and all the way to the back. People were standing and sitting on the stairs. As the last details were ironed out, I chatted with the crowd a bit about the significance of the flowers. When the bookstore manager signaled that we could start, I asked “Could someone please go and get Joanna?” and everyone laughed. Hostess to the end, she was standing by her post.

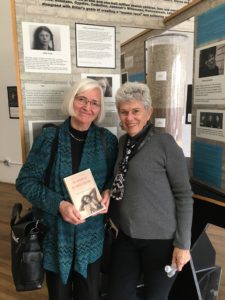

Photo by Karen Pike

Tod Gross, Phoenix Books’ manager, welcomed everyone, followed by Cheryl Herrick, who introduced me and mentioned a crucial moment in my early life. I was standing in the schoolyard of Carr Junior High School in Durham, North Carolina on the day when the first African American student was to enter the school. She was by herself, being jeered and taunted. Would I collude with the others by minding my own business? Would I add to their noise or tell them to stop? Or would I stand beside her? These are the same questions that An Address in Amsterdam explores, in a different place and time.

Maybe that’s what made me feel at home in Amsterdam, and in the terrible world of 1940-45: the combination of great beauty and great suffering, and dilemmas where absolutely nothing is black and white, where there are often few good choices, and the examples of courage are rare but utterly remarkable. As I spent hours in archives and museums and wandering the canals to find significant addresses on five long visits, the world of that time became clearer and clearer to me. When I saw a photograph of trees whose limbs had all been amputated, for example, I said “Oh, it must have been during the Hunger Winter.” Sure enough, the date was the terrible winter of 1944-45, when more than two thousand Amsterdammers starved to death, and there was no fuel to heat their homes.

As I read and spoke at the book launch, I tried to give people the feel of both aspects of An Address in Amsterdam: the suffering of the characters and the city itself, but also their courage and resolve, their refusing to let themselves be completely robbed of love and beauty in their lives. The heroine, Rachel, begins as a naïve 18 year old who doesn’t understand that she’s falling in love, but a year later she is already working for the underground and grows up very fast. Although only a handful of people resisted as Rachel did, they deserve our respect for the risks they took, and their persistence even in the worst of circumstances.

Photo by Karen Pike

In my research, I learned about more and more individuals who had been murdered: 80% of Jewish people in the city of Amsterdam, plus the resisters and others whom the Nazis hated. I began to miss them. I began to imagine them here and there, their fish stalls and doctor’s offices and cabarets and galleries and orchestras. Part of my work was bringing them back to life, not just at the moment of deportation and death, but before that, when they were still struggling and loving and enjoying life.

The launch audience asked serious questions: about the woman on the cover of the book, when I realized that it wasn’t enough to portray the suffering and mass murder, how I constructed scenes by getting “into” the characters, what it was like for me as a Gentile to write about a Jewish character, how people in the Netherlands might react to the book. I answered for a while, then thanked everyone and asked them to please spread the word. Every book had a flyer in it to suggest how to do that, as well as a stamped post card. I closed with some thanks, and it was only then that I broke down, remembering my great friend Eliane Vogel Polsky, who was hidden in plain sight as a Belgian teenager, and was the midwife for this book. She asked about it in our final conversation a year ago.

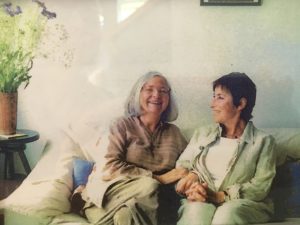

Mary and Eliane in Amsterdam, photo by Karen Pike

Upstairs, the line for book signing snaked along for what seemed like miles. How I loved composing those inscriptions! As I saw that I needed to speed up, I said “Someday I’ll just write ‘Best wishes’, but tonight I’m going to do it right. These are my friends.” Several people said “This is for my aunt,” “This is for my friend who’s in the hospital,” “This is for my daughter.” I loved the feeling of the book going out and away in so many directions that I couldn’t even imagine. Rachel, who represents so many young Jewish women who were killed, is alive and traveling.

The icing on the cake: Tod, the bookstore manager, asked me how many books I thought we’d sold. “Forty,” I said optimistically. “Ninety seven,” he said, “almost a book a person. Some people bought multiple copies, but even so. We never see that. 25% is what we expect, 50% is really good.”

I come from the maritime people of eastern Canada, so the metaphor of the launch appeals to me. I’ll never go back to the shore of being a writer rather than an author. Now I’m afloat, and so is my ship. It has been built, plank by plank, from pieces gathered in many times and places. The ship has slipped down the pathway made for it, and has splashed into the water, where it is swaying and eager for the sea. Where it may go is a mystery. My best hope is that the book will be taken seriously both as a good, deep story about a brave young Jewish woman, and as a warning about how quickly an open, liberal city can change. When hatred and violence threaten, An Address in Amsterdam shows that anyone can take courageous action, in our own place and time.

The last few days fulfilled my longtime dreams of what I might do as a writer in the world. Being with two groups in New Mexico to discuss the importance and possibility of resistance gave me a sliver of hope, even ten days before Donald Trump’s inauguration. If there are 35 people in a red state in two locations who are receptive to that message, we need not despair for our country. Around the talks, I got to visit with dear old friends, see countryside utterly different from my usual haunts, appreciate the marvels of sandhill cranes for the first time, and learn from the Pueblo Native Cultural Center in Albuquerque.

The last few days fulfilled my longtime dreams of what I might do as a writer in the world. Being with two groups in New Mexico to discuss the importance and possibility of resistance gave me a sliver of hope, even ten days before Donald Trump’s inauguration. If there are 35 people in a red state in two locations who are receptive to that message, we need not despair for our country. Around the talks, I got to visit with dear old friends, see countryside utterly different from my usual haunts, appreciate the marvels of sandhill cranes for the first time, and learn from the Pueblo Native Cultural Center in Albuquerque.