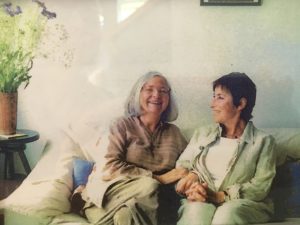

Today would have been my best friend’s 91st birthday, and she would be mad at me for crying about it. But there’ll never be another Eliane Vogel Polsky, for me or anyone. I’ve even forgiven her for keeping a secret from me for 19 years.

I first admired Eliane as a professional mentor – a labor lawyer who devoted herself to the cause of women’s rights and won landmark cases in the EU, a distinguished law professor who oversaw all the EU-funded research to improve women’s employment in Europe. The first day we met in Brussels, I fell under her spell – an elegant, brilliant woman, not one to suffer fools gladly but with the warmth and generosity of a huge bonfire. There was no hint of what I would learn about her later.

An hour with Eliane was like a month with anyone else, so intense was her attention to any given moment. Taking a walk in Brussels, her home city, brought forth a stream of stories about the garret room her father reluctantly allowed her to rent so she could have some privacy before she married, about the cascades that used to rush from the fountains in the center of the city.

Over the years, we became ever closer – especially after Eliane retired, and was free to come to the U.S. every year. Our conversations had, I thought, covered everything. Then I spent a week with her before my first long stay in Amsterdam in 2001, and she told me something she had never revealed before. As a Jewish teenager, Eliane had been hidden in plain sight in a convent school in Liege. She took me to that classically beautiful city, a river town. This time, her stories seared rather than delighted me. We saw the train station where she was almost caught without her false papers. The bridge where the Nazis had made “une piege a soucieres – you know what it is? A mouse trap.” The convent itself.

If Eliane had told me that she’d been kidnapped by pirates, I couldn’t have been more astonished. I had simply never done the arithmetic to realize that of course she would have had to hide. For the first time, I felt the truncheon of Nazism crash down on my head. They would have killed my best friend, a woman of endless accomplishment and dearer to me than I can ever express.

So when I went to Amsterdam the next week for a long stay, I was open to learning about the Nazi occupation as never before. After discovering that we were living inside the Jewish Quarter, I began to research it in earnest. Over the coming 13 years as we came and went from Amsterdam, Eliane visited often from Brussels. Our 2002 flat was under an attic where Jewish people had been hidden. I was so haunted that I had to learn more about their world and write about it for others. Rachel Klein, the heroine of An Address in Amsterdam, and her parents began to appear to me, not in the supernatural sense but in some ethereal way that characters come to writers.

Eliane played a crucial role in developing the book – not only because I was so disturbed by her own relatively narrow escape, but because she told me many more stories about that time. For example, she recounted the reluctance of her father, a decorated World War I veteran, to believe that their family could possibly be vulnerable; or how it felt to be a 15 year old keeping a huge, terrible secret from absolutely everyone except the Mother Superior in the convent school. Her sensibility, her sense of her predicament, her fear and courage are all woven into An Address. As I wrote, Eliane read my work to see whether it “rang true,” and read the revisions until they did. She accompanied me to exhibits and sites even though they disturbed her and gave her bad dreams.

In our very last conversation, she asked me about the book, and I promised that it was coming. It was, but she died a year before An Address in Amsterdam was published – the story of a young woman with Eliane’s spunk and love of life, who never lets fear stop her.

When Eliane died the death of the just, surrounded by her children and grandchildren, even I could accept that it was time. Most days, but not today.