This time, I’d like to send a more personal letter than usual, in keeping with the contemplative nature of “sheltering in place.” As one of my friends wrote me, “We are all given this once in a lifetime opportunity to reassess how we use our time on earth.” I miss meeting people in person to reflect on the complexities of Amsterdam in 1940-45, and what we can learn from those times, especially the resistance. Thank you for being one of the people who has shared that experience with me and made it possible.

May 4 is particularly a time of reflection, because it is the Day of Remembrance in the Netherlands. It is meant to honor everyone who died in World War II, including particularly the 104,000 Jewish people and others who were murdered in the Holocaust. I’ve been to many deeply moving commemorations over the years: an art ritual in a park surrounded by streets once full of Jewish people (http://maryfillmore.com/tag/art-ritual/), a neighborhood event beside a small memorial to local citizens who were randomly executed, even the huge crowd with the Queen (at that time, now the King) at Dam Square. Here is the scene as it was this year:

What has always affected me most is the two minutes of silence at eight o’clock in the evening, still broad daylight in Amsterdam with its gardens burgeoning with late tulips, the canals lined with elms in their new-leafed finery. The trams, the bicycles, the cars, even the people come to a halt. Even the legendarily prompt Dutch trains stop running. My dearest friend Eliane Vogel Polsky, herself hidden in plain sight as a Jewish teenager, was once traveling from Brussels to Amsterdam to visit us on May 4. The conductor announced the two minutes of silence and asked people’s cooperation. To Eliane’s astonishment, even the teenagers playing cards at a nearby table stopped and sat quietly. She was in tears when she told us about it. To her, it was an affirmation that the great suffering of that time had not been forgotten.

“These are little people. They can only kill us.” Rabbi Frank

Now that she, my best friend, is gone, I feel that I must use those two minutes of silence well. My years of study of the Holocaust and resistance gave me both a darker view of what people are capable of, and a vision of how, even in the most terrible times and under extreme pressures, human generosity and even valor break through. Think of Rabbi Frank who told his imprisoned and terrified congregants, “These are little people. They can only kill us.” Or of the ten Boom family and so many others like them, hiding their neighbors in peril of their own lives. When the Nazis threatened Corrie’s father with execution, he replied “It would be an honor to give my life for God’s ancient people.”

Reorienting Ourselves

What can we do to be worthy inheritors of those we remember on May 4? We are living in a moment when the noble thing to do is stay home, wash our hands, wear a mask when we go out, and support others at a distance. It doesn’t sound like much beside the Dutch Resistance, does it? And yet it is what our times call for – that, and reorientation from our busy-busy, overconsuming lives that are literally costing us the earth. That difficult task, and resisting the political insanity of our times, is worthy of our gifts. At the most intimate level, I am acutely aware that these days may give me my last chance to be kind to a neighbor I don’t especially enjoy, to tell and show the people I love how important they are to me, and particularly to leave an impression in the hearts of the children who might not know me when they are older. But I also must be thinking in the most long term sense, how to extend the reprieve we have given the earth by not driving and extracting and smashing, so that both humans and all the other creatures can flourish differently. What would that reprieve mean for me, as an individual, for my country and the world? That’s where I need the courage the Dutch resisters had.

This year, a double hush falls at this moment: the calm the pandemic has demanded of us, and the remembrance the dead deserve from us. Each of us can find the way toward right action at this time. Will we have shone light for others? Can we find ways, as so many people in hiding (Jewish and Gentile) did, to make a life of purpose and dignity in confinement? Can we address the desperation of those who need food and rent and succor? So much is at stake. We are in the kind of predicament that can topple even strong democracies.

Let’s find strength in ourselves, in the dead, and in each other. Somehow, as they did, we will find a path. Thanks for staying in touch with me and be well,

Mary

P.S. The New York Times had a wonderful article recently about bringing Dutch wartime diaries out of the archives where they were buried thanks to volunteers: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/15/arts/dutch-war-diaries.html.

I reacted to it by writing about “Listening to Dutch Ghosts as We Shelter in Place” below, at http://maryfillmore.com/listening-to-dutch-ghosts-as-we-shelter-in-place/.

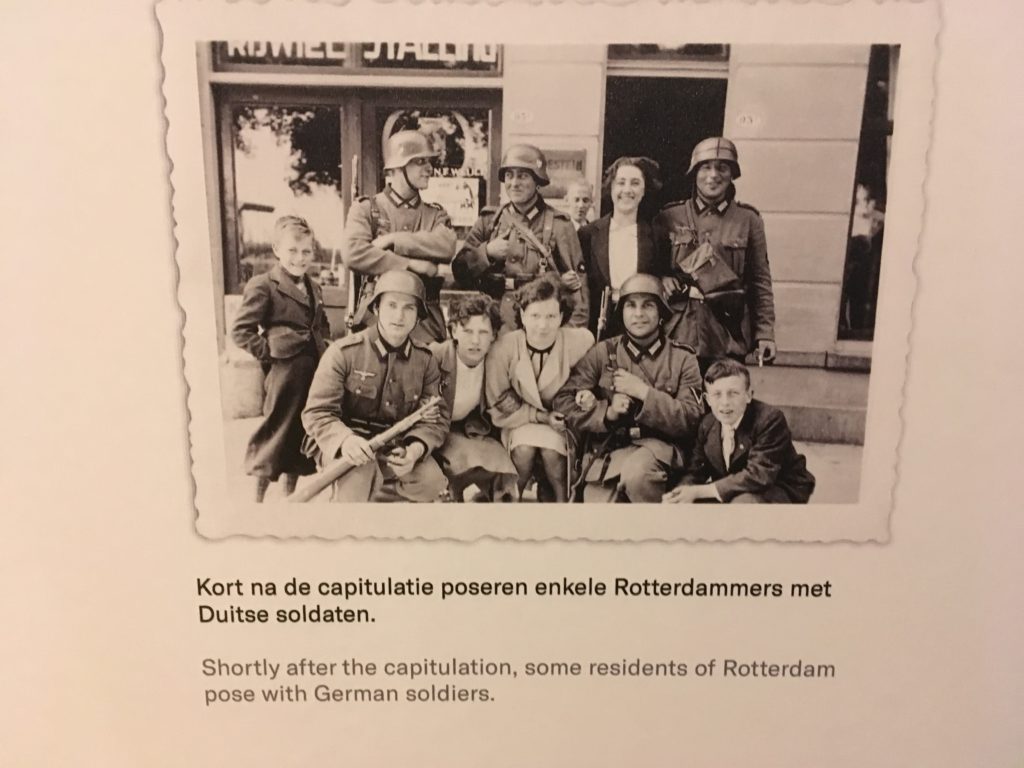

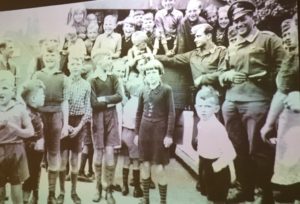

With foreknowledge, it was poignant to see photos of the children of Arnhem gathered as the Germans arrived, with one soldier smiling broadly. How many of those kids would survive one of the bloodiest battles of the war,

With foreknowledge, it was poignant to see photos of the children of Arnhem gathered as the Germans arrived, with one soldier smiling broadly. How many of those kids would survive one of the bloodiest battles of the war,