Westerbork train track with flowers laid along it on Remembrance Day

Only 77 years (almost to the day) after the first Dutch train hauled people to the extermination and concentration camps, the Dutch Railway has agreed to pay reparations to 500 remaining Jewish, Roma and Sinti survivors and their widows/ers or children. The railway will also seek ways to honor those who didn’t come back and left no one. The Dutch Railway (NS) allowed the Nazis to buy their services unless it compromised their principles (whatever that would have meant), and the unions followed suit. They made about 2.5 million euros in today’s currency.

Reparations are not offered now because of a sudden change of heart – after all, Dutch Railway apologized in 2005, sixty years after the end of the war. Rather, it is thanks to the intervention of Mr Salo Muller, a Holocaust survivor and physical therapist to the Ajax soccer team, who pushed for monetary compensation comparable to that of the French Railway. Rather than pursue legal action, the Dutch Railway established a committee under the leadership of former Amsterdam Mayor Job Cohen, himself a Jewish hidden child.

Mayor Job Cohen on bike

Their recommendation has just emerged, and they will be responsible for overseeing the disbursements. “It is not possible to name a reasonable and fitting amount of money that can compensate even a bit of the suffering of those involved,” Cohen said in a statement. Each survivor who was transported will receive 15,000 euros ($17,000) each. Widows and widowers of victims are eligible to receive 7,500 euros ($8,500) and, if they are no longer alive, the surviving children of victims will receive 5,000 euros ($5,685).

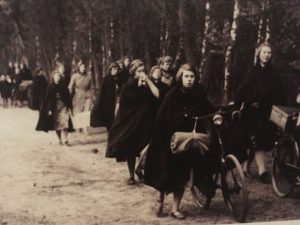

What do we know about the role of the trains in the deportation? Between midnight and three a.m., the Dutch Railway ran a special series of trains beginning in July 1942 from Amsterdam’s Centraal Station to a station near the Westerbork Transit Camp. There was special provision for the train employees to be exempt from the curfew. It’s important to remember that initially almost everyone believed that they were headed for labor camps, not their deaths.

Centraal Station Amsterdam

The next train, however, was more sinister: the classic cattle car strewn with filthy straw and occasionally a passenger carriage. Once a week, on Tuesday, the train pulled out of the station (first nearby Hooghalen, then Westerbork itself once a spur had been added) with its load of victims, the number chalked on the side. The process for deciding who would stay and go is barbaric, but not the responsibility of NS. In the first six months (July 1942-January 1943), an astute medical orderly noticed that the car was always the same, and he created an inconspicuous hiding place where messages could be transmitted. Moreover, he kept copies as well as transmitting the originals, and thanks to him we have an account of the conditions on the train. One person wrote “When the door was shut, the smell was unbearable and the air oppressive; when the door was left open, there was a horrible draught. . . [overnight] two had died of cold and misery. They were taken to the luggage section.”

Last Train from Westerbork

The resistance fighter J.H. Scheps asked what the train employees felt when they heard the pleas and cries of their passengers: “Don’t you understand what they are doing to these helpless Jews? Don’t you know how they torture our Jewish comrades? Have you bread and butter patriots never heard the voice of Rachel, she who mourns and will not be comforted for her children – the children you help to carry to their death?” If only one could look back and find resistance to the deportations among the train management or workers.

From July 1942 until September 1944, ninety-eight trains rolled out on time. Of the passengers, not a single one survived on 26 transports, and many others had one person alone. Depending on which numbers you believe, the trains took away between 104,000 and 110,000 people from the Netherlands, and only 5,450 returned.

Westerbork monument representing lives lost

When, after the war, the Enquiry Commission confronted the Dutch Railway Board with its choices, the response was that the question of deportation had been raised, but no one had ever urged them to refuse cooperation. Who could have done that? The Board itself, the workers, the union leadership? I hope that a person who reads this knows of that rare someone who did speak up, and will tell us about it. And I hope someone else who is in a position to stop something they know is wrong will take this story as a warning.

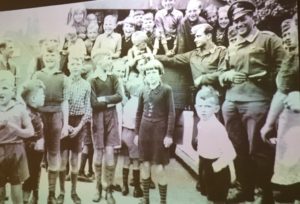

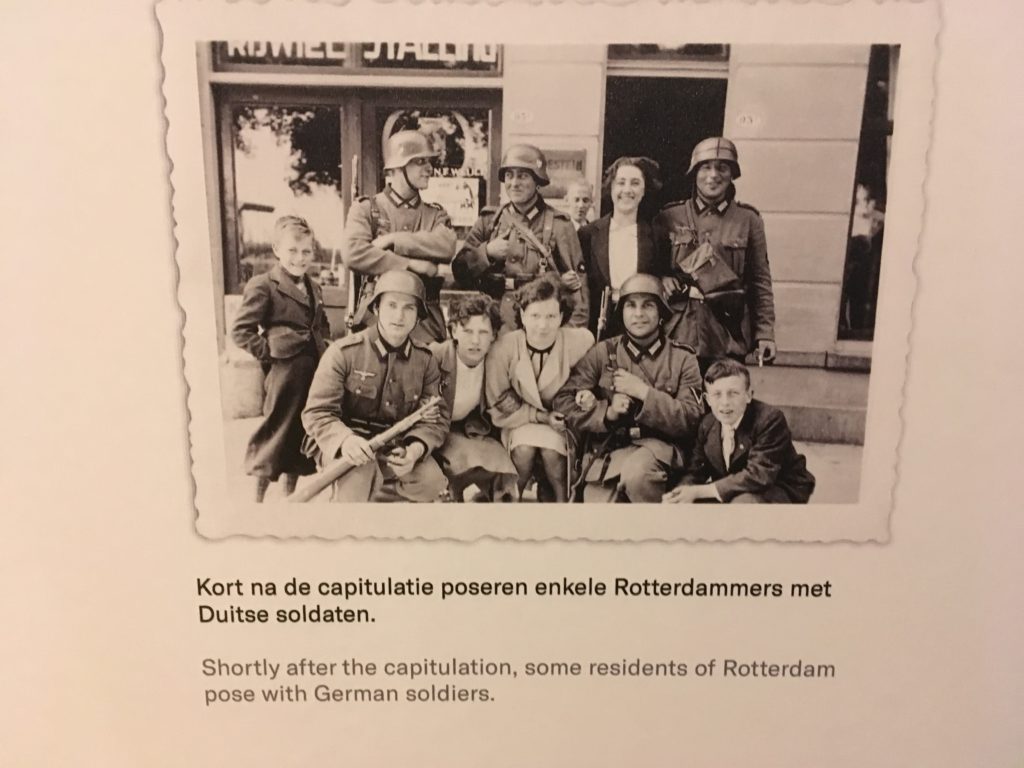

With foreknowledge, it was poignant to see photos of the children of Arnhem gathered as the Germans arrived, with one soldier smiling broadly. How many of those kids would survive one of the bloodiest battles of the war,

With foreknowledge, it was poignant to see photos of the children of Arnhem gathered as the Germans arrived, with one soldier smiling broadly. How many of those kids would survive one of the bloodiest battles of the war,

We crossed the bridge and turned right. Eerily, the warning sounds that the bridge was about to be lifted bleeted loudly. This is the same bridge the Nazis raised to isolate the Jonas Daniel Meijerplein for the first roundup. Walking along the Nieuwe Keizersgracht, a small residential canal, we saw the markers at our feet which show the name and age of each person who used to live in the house opposite us. All had been rounded up and murdered. Every few feet, someone quietly read the names.

We crossed the bridge and turned right. Eerily, the warning sounds that the bridge was about to be lifted bleeted loudly. This is the same bridge the Nazis raised to isolate the Jonas Daniel Meijerplein for the first roundup. Walking along the Nieuwe Keizersgracht, a small residential canal, we saw the markers at our feet which show the name and age of each person who used to live in the house opposite us. All had been rounded up and murdered. Every few feet, someone quietly read the names. The clomping of the horses’ feet and the drums sounded louder, and those still reading the plaques could see the crowd advance over the bridge. We passed near the Carré Theater where numberless Jewish people performed, and crossed The Skinny Bridge, looking back up the River to the plaza where we had begun. It was once a medieval Jewish neighborhood, torn down over great protest to build the City Hall/Opera House.

The clomping of the horses’ feet and the drums sounded louder, and those still reading the plaques could see the crowd advance over the bridge. We passed near the Carré Theater where numberless Jewish people performed, and crossed The Skinny Bridge, looking back up the River to the plaza where we had begun. It was once a medieval Jewish neighborhood, torn down over great protest to build the City Hall/Opera House. nutes to acknowledge us, but few stayed out. It was too cold. The flags were all at half mast.

nutes to acknowledge us, but few stayed out. It was too cold. The flags were all at half mast.