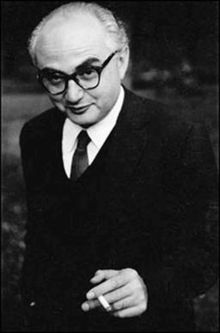

Amsterdam’s Jewish Historical Museum has mounted a brilliant exhibit about “Chim,” or David Seymour as he was later known. He was an early photojournalists and founder of Magnum, a man who suffered the torments of his century and circumstances, and made the suffering of others, especially children, real to the comfortable. Born Jewish in Poland in 1911, he studied science at the Sorbonne and began taking pictures more or less by accident. His depictions of the Spanish Civil War are riveting, including and especially his portrait of Dolores Ibarruri, La Pasionaria, one of the founders and leaders of Spain’s communist party who famously declared “They shall not pass,” a phrase we still hear at demonstrations today.

Because of the Nazi threat, Chim left Paris in 1939 with a shipload of Spanish refugees on their way to Mexico. His photo of a refugee woman writing a letter on top of her suitcase is as haunting as that of a little girl with her two dolls, her face a study in insecurity. Chim joined the U.S. Army and was stationed in England to decipher aerial photos for the duration of the war, but his great moment came afterward. The newly formed UNESCO commissioned him to do a series on “Children of Europe,” which at that time included 12 million war orphans. In six months, Chim captured classic image after classic image. There’s an extra poignancy to them because everyone in his family in Poland was rounded up and murdered, and because he never had children of his own. This didn’t stop him from “adopting” many along the way, often staying in touch for years. So the “Children of Europe” literally became his family. He moved from that project to document the early years of Israel as well as doing some portrait photography, but was killed in 1956 by Egyptian machine gun fire four days after the Suez Crisis was supposedly resolved.

As we toured the exhibit, I recognized some photographs I remembered from my childhood reading of “The Family of Man”. I pored over it often, and asked my parents to explain specific images to me. The book collected the photos in the 1955 exhibit at MOMA, which aimed to show the commonality of all human beings despite our obvious and apparent differences – showing us at play, in marriage and death, at work, and so on, with quotations from all around the world. Some are still with me: “She is the tree of life to them.” “If I did not work, these worlds would perish.” “Beauty before me, beauty behind me, beauty all around me.” And so are some of the images – including one that Chim took of an old man making the letter A. My mother spent a long time explaining to me that some people are illiterate, and that it is never, never too late to learn something new. In the exhibit, I also recognized a photo of a vibrant young woman dressed in white playing the violin and leading a line of similarly attired toddlers who are hanging on to each other. There is a gaiety to it that belies the fact that they were victims of war being fed by a charity. Again and again, Chim reaffirms the human spirit.

We crossed the bridge and turned right. Eerily, the warning sounds that the bridge was about to be lifted bleeted loudly. This is the same bridge the Nazis raised to isolate the Jonas Daniel Meijerplein for the first roundup. Walking along the Nieuwe Keizersgracht, a small residential canal, we saw the markers at our feet which show the name and age of each person who used to live in the house opposite us. All had been rounded up and murdered. Every few feet, someone quietly read the names.

We crossed the bridge and turned right. Eerily, the warning sounds that the bridge was about to be lifted bleeted loudly. This is the same bridge the Nazis raised to isolate the Jonas Daniel Meijerplein for the first roundup. Walking along the Nieuwe Keizersgracht, a small residential canal, we saw the markers at our feet which show the name and age of each person who used to live in the house opposite us. All had been rounded up and murdered. Every few feet, someone quietly read the names. The clomping of the horses’ feet and the drums sounded louder, and those still reading the plaques could see the crowd advance over the bridge. We passed near the Carré Theater where numberless Jewish people performed, and crossed The Skinny Bridge, looking back up the River to the plaza where we had begun. It was once a medieval Jewish neighborhood, torn down over great protest to build the City Hall/Opera House.

The clomping of the horses’ feet and the drums sounded louder, and those still reading the plaques could see the crowd advance over the bridge. We passed near the Carré Theater where numberless Jewish people performed, and crossed The Skinny Bridge, looking back up the River to the plaza where we had begun. It was once a medieval Jewish neighborhood, torn down over great protest to build the City Hall/Opera House. nutes to acknowledge us, but few stayed out. It was too cold. The flags were all at half mast.

nutes to acknowledge us, but few stayed out. It was too cold. The flags were all at half mast.