A Praise Song for Karen Tishuk

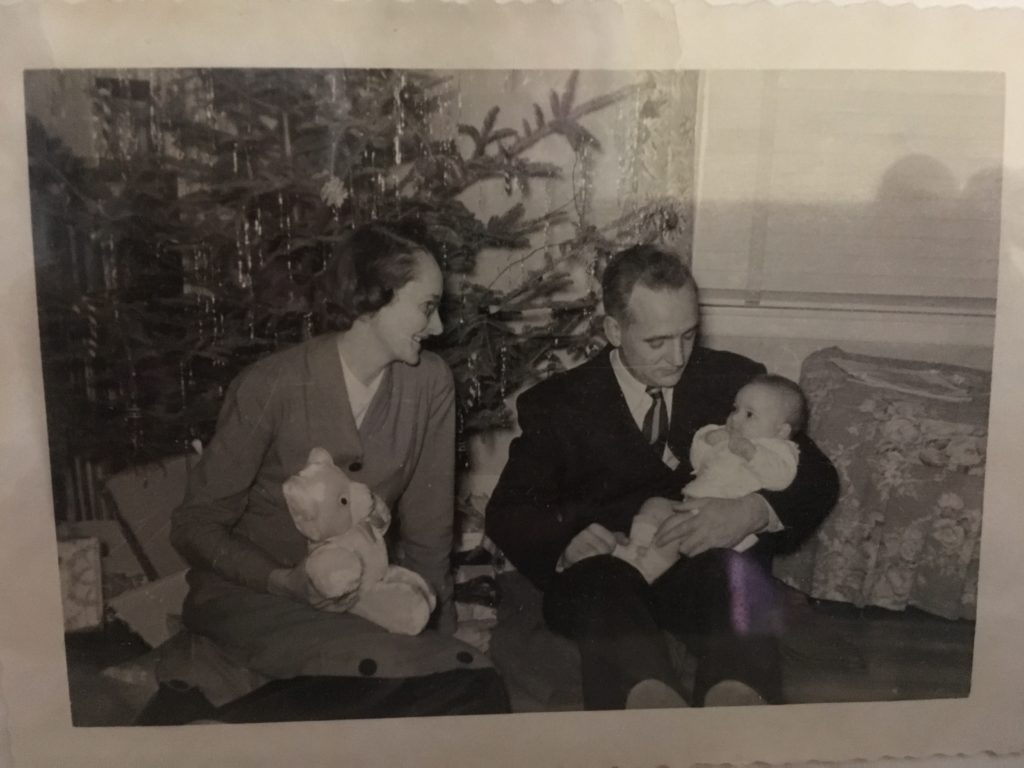

Karen and Mary, December 2017

Even in her last shortened months of life, Karen Tishuk began many sentences with “I’m a nurse, so I noticed . . .” She was observant, she listened, and when times were tough she knew what to do – even when she was diagnosed just shy of 70 with cancer and a lousy prognosis. By the time she died just nine months later, she’d used everything she learned as a hospice nurse and more. She gathered a bouquet of friends from an extraordinary and geographically scattered life to support her all the way to the end.

Karen had a conventional upbringing in Wisconsin in a big Catholic family, but she didn’t fulfill her destiny as a Midwestern housewife. From the beginning, she was an odd duck in her family despite mutual affection. She loved the lake she lived by, and made an early connection with nature and the earth that lasted until the day she died. Everything in her life flowed from this central, most crucial relationship.

Karen chose to be a professional woman, a nurse. She moved politically far to the left of her family of origin, taking action on multiple issues of justice. Just as profoundly, Karen felt a call to several Native traditions, which validated her longstanding attunement to the earth. Her days always began with meditation and alignment with the larger forces embracing the human world. Karen had to spend time outside, regardless of weather or inconvenience or busy-ness. She brought friends and patients the assurance and calm that stemmed from those hours of meditation, prayer and being in nature. Over time, Karen developed her own gifts to do readings and numerological analyses for others. When she discovered that the focus of her life was women, she came out as a lesbian and feminist.

Unlike anyone else in her family, Karen chose a nomad’s life. She spent a year or two or three in a place, working as a nurse (often in hospices), getting to know the land, and making close relationships that often lasted. A person of remarkable adaptability, she lived to my knowledge in Alaska, Hawaii, Arizona, New Mexico, Massachusetts, Colorado, Washington, Oregon, and Vermont – and I’m sure I’m missing some. Karen made herself at home wherever she went, and could always return to open arms. We met during the Vermont chapter from 2011-15, at the end of her career as a nurse.

Lake Champlain, Vermont

Karen and I laughed a lot about our differences. She was far more “woo-woo” than I, and yet I observed that her intuitions about people and situations were often uncannily right. Although my path has been guided more by my brain and heart than dreams or visions, I respected Karen as someone who took risks that most of us avoid. How many of us really let inner guidance determine our paths? Karen lived by the Taoist maxim, “She who obtains has little. She who scatters has much.” In contrast, I am a nester and even a hoarder of sentimental artifacts (Karen only had a few, but how she loved them!). For all our differences, our common politics and our joy in being out in nature brought us together again and again. We walked and talked for miles: in our urbanized neighborhood of old farmhouses, in a nearby graveyard with tall cypresses and marble monuments, along footpaths in hushed Vermont forests or beside the vastness of Lake Champlain.

Both of us were also outsiders in another sense, grappling with our place in the world and how to live with our wanderlust. As Karen aged, how would she accommodate that desire to “hit the road again”? What if her body said no at some point? But it hadn’t yet. She was as healthy as a farmer’s strongest horse. We also ranted about politics, and remembered better times, i.e. the sixties, when there was a real Movement. But we also noticed innumerable petite wildflowers and flashes of songbirds along the way. We wandered across the Canadian border to Montreal and Frelighsburg, savoring food seasoned with the “je ne sais quoi” of French ancestral knowledge, and drinking in the art. Karen relished both art museums and seeing her friends’ treasures.

Whenever there was a project at hand, Karen pitched in. Her sturdy body, descended from women who took pickaxes to the prairies, was almost as strong as her will. Her lively, broad face accented by her pixie-cut light brown hair always showed determination, no matter what she was undertaking. To be enfolded in her embrace meant a full body experience, and she tackled any task with that wholeheartedness and physical competence. When she held a baby, it wriggled happily and settled right down in response to her animated face and assured gestures.

Karen on right at Mary and Joanna’s wedding, July 14, 2013

My partner Joanna and I will always enjoy the cherry tree Karen planted for us, and the memories of her role in our wedding, just a few weeks after the Supreme Court decision creating equal marriage in the U.S. It meant so much to Karen that it was possible for us to be married, and as always Karen bustled about to make sure everything went smoothly. No celebration was complete without her, birthday or otherwise. In the co-housing community where we all lived, Karen was constantly on call for residents with health issues, especially two who were fighting terminal cancer.

Like me, Karen was a reader of both prose and poetry, and we spent many hours talking about books. I took daily comfort in glancing across the broad lawn that separated my study and her bedroom (both on the second floor). As I worked, I could see Karen in her rocking chair with a book. Even though she wasn’t paying attention to me, I felt her presence. I knew that she had regular phone calls with her faraway friends, and I hoped I might be among them when she moved away one day. Karen didn’t love Vermont; she’d come here because of a vision, but she longed for the big vistas of the west, to gaze on the great mountains and deserts that were her spiritual home. Her face glowed whenever she said “When I lived in Santa Fe. . .” or “While I was a nurse in Sedona. . .”

To say that Karen lived simply is an understatement. She never had more “stuff” than would fit in her car, and she got rid of many items along the way so she could travel light. When Karen drove from Vermont to Oregon, I don’t think she had to ship anything. Almost everything she had was beautiful to her, often carrying a story with it. In her last home, she walked me from object to object. They were suffused with the story of her whole life, an index of her important relationships. She might not have had enough pots and pans (in my view), but she had a magnificent multi-colored statue of Green Tara sitting on real silk for her altar. Although Karen had had more prosperous times, in the period when I knew her money was always an issue. She had lost her savings in the crash in 2009, and was working less than she wanted to in Vermont, as an overqualified professional near retirement age.

After Karen left New England – called back to the west, first to Eugene and then to southern Oregon – we stayed in touch, always at birthdays and anniversaries. Nobody found more apt cards than Karen, and her messages were heartfelt, fulsome reflections on what she loved and admired about us. Never trite, always specific, she touched on the essence. In our phone conversations, she tracked our lives with detailed memory, never forgetting an important person or event. It was humbling. Sadly, in January 2017, Karen fell and hurt her leg badly, and I stayed in closer touch after that time. It slowed her making friends in her new Southern Oregon location, as well as limiting her ability to be in the wild open spaces she loved.

It must be repression that I cannot remember how I learned, in late November 2017, that Karen had been diagnosed with serous uterine cancer metastasized to the cervix. I do remember, in Karen’s own voice, her account of the moment the nurse examining her let out a soft “uh-oh” when she felt the cervix. Further testing confirmed her instincts, and a hysterectomy was scheduled on December 14. In typical Karen “superwoman” fashion, her plan was to drive 3 hours to Eugene, do the pre-operative preparations, stay overnight in a hotel, have the surgery, and drive back that night – or maybe one more night in the hotel if she was feeling a bit under the weather. I asked if anyone out there could accompany and support her for those days. She said no, and I went.

When Karen met me at the hotel she’d reserved for us, she was agitated and exhausted from all the preparations, but happy to see me. I suggested a walk, since she’d thoughtfully put us right by a silvery river and a city park that was still green despite the onset of winter. Walking had always helped us before. We meandered alongside the water, watching the ducks and their antics, and admiring the lean beauty of the deciduous trees. We had a delectable local meal that night, something Karen had always enjoyed, and the next day another walk in an extensive park with huge conifers and a former filbert orchard. At times she was preoccupied, but we had many joyous moments as we wandered. “I see why you insisted that we get here in time to enjoy ourselves,” Karen admitted before we went to the hospital for pre-op. I had been through cancer with a friend before, and I knew we might never have fun again in the same way, and that she might never or almost never feel as well as she did at that moment. But I didn’t say that, of course.

When Karen met me at the hotel she’d reserved for us, she was agitated and exhausted from all the preparations, but happy to see me. I suggested a walk, since she’d thoughtfully put us right by a silvery river and a city park that was still green despite the onset of winter. Walking had always helped us before. We meandered alongside the water, watching the ducks and their antics, and admiring the lean beauty of the deciduous trees. We had a delectable local meal that night, something Karen had always enjoyed, and the next day another walk in an extensive park with huge conifers and a former filbert orchard. At times she was preoccupied, but we had many joyous moments as we wandered. “I see why you insisted that we get here in time to enjoy ourselves,” Karen admitted before we went to the hospital for pre-op. I had been through cancer with a friend before, and I knew we might never have fun again in the same way, and that she might never or almost never feel as well as she did at that moment. But I didn’t say that, of course.

If ever someone had already paid their karmic debt in helping others, it was Karen. She did years of hospice work as well as helping informally, as she did at cohousing, with the many crises that happen on the cancer path. I thought of all that as I waited for the surgeon to come and talk to me after Karen’s operation (I had medical power of attorney at that time). When he finally appeared, he said she’d done well in surgery, and would start chemo as soon as possible for six months, then a course of radiation. I asked about prognosis. “She’s got a fighting chance, about fifty-fifty – well, no, let’s say 40%. Maybe 35%. But she’s a fighter.”

To my huge relief, he decided to keep her overnight in the hospital, and we spent one more night at the hotel before I drove her home through the mountains. It took us much of the day with all the stops we needed to make. Throughout the medical saga, and even as we traveled home, I watched Karen learn the name of almost every single person she encountered. And she asked questions, learned something about everyone she met, even if it was just superficially. Did any of the surgeon’s other patients know he was about to adopt a foster child? She connected with the clerk in the hokey “family restaurant” where we stopped for lunch on the way home, with the inept nurse who wasn’t changing a tube right in the hospital, with the kid who helped her with a parking sticker. That was how she operated – and even a pit stop was the occasion to admire the views into the distant mountains.

Fortunately, Karen received a modest inheritance from her mother soon after she was diagnosed, just in time to cover the many expenses that insurance wouldn’t touch, including alternative therapies. Karen wasn’t a saint; she was furious that cancer intervened just at the moment when she was approaching her 70th birthday and had a bit of spare cash to do some things she’d always wanted to do. Over the next nine months, she put together a small group of women from around the country who would sustain her. Robyn from Santa Cruz was her most frequent visitor and caller, a craniosacral therapist who became the first medical power of attorney with me as backup. Shari from Philadelphia has her own yoga studio and was constantly providing chants and prayers that Karen could join in. Shari’s sister Susan from Sedona stayed in constant touch, and sent Karen photos from her extensive hikes they used to take together. The other Mary from Wyoming was a sister nurse with whom she could discuss medical strategy and drug issues. My job was to provide poetry sometimes and love always, and to check out the doctors’ claims and prophecies against the actual research. I was the sometimes unwelcome voice of the future, trying to anticipate what Karen might need and stay one step ahead of it. Over time, our circle expanded – especially toward the end – to encompass others, including her marvelous hospice nurse friends from Seattle and elsewhere. Robyn set up a Caring Bridge site early on so that many people could be in contact, including Karen’s family, and she drew a lot of strength from that.

Joanna and I went out to visit Karen for a week in late February, while she was going through chemotherapy. Despite her weakness and digestive issues, we managed to travel to see the majesty of Mount Shashta, a looming presence encased in snow just across the California border. The three of us stood in awe on a bright winter day. Even 25 miles away, we felt the presence, and Karen was in her element. A few days later, she took us out for an extravagant and scrumptious dinner in an historic inn in nearby Jacksonville. We ate by firelight in a cozy room with rustic stone walls. Karen had even chosen the specific, secluded table. Although she threw up later, she thoroughly savored her lamb chops and potatoes Anna. Some pleasures are worth it. At her home, I cooked gallons of bland soup and bone broth and froze it, and Joanna hung curtains, fixed electrical issues and created calm.

Joanna and I went out to visit Karen for a week in late February, while she was going through chemotherapy. Despite her weakness and digestive issues, we managed to travel to see the majesty of Mount Shashta, a looming presence encased in snow just across the California border. The three of us stood in awe on a bright winter day. Even 25 miles away, we felt the presence, and Karen was in her element. A few days later, she took us out for an extravagant and scrumptious dinner in an historic inn in nearby Jacksonville. We ate by firelight in a cozy room with rustic stone walls. Karen had even chosen the specific, secluded table. Although she threw up later, she thoroughly savored her lamb chops and potatoes Anna. Some pleasures are worth it. At her home, I cooked gallons of bland soup and bone broth and froze it, and Joanna hung curtains, fixed electrical issues and created calm.

Over the months that followed, Karen assembled a professional team which included both allopathic and more traditional healers, some of whom were “hands on” and others who worked energetically or even long distance. Toward the end, she found an Oriental medicine practice which provided a lot of relief and comfort. Karen’s spirits went up and down. She’d always had energy to burn, and suddenly she didn’t. She’d loved good food, and it didn’t always taste right. Even if it did, she couldn’t digest it. Her bowel problems increased, as well as the pain and inconvenience that accompanies those. When her oncologist told her chemo wasn’t working any more and proposed a different regimen, Karen first agreed, then declined based on research showing the odds just weren’t good enough to put up with still more side effects.

Mary and Karen at her apartment, February 2018

All along the way, Karen received a steady stream of calls, texts with quotations or news or (her favorite) photos or videos, e-mails, cards, and gifts of both sacred and profane items. She had to conserve her energy, so passive communication was often best – including Caring Bridge, which she checked every day that she wasn’t truly sick and sometimes when she was. The messages of caring and support meant so much to her, but she also had a strong appetite for distraction. Who wants to think about illness all the time, especially when they’re sick? Karen wisely decided to take Sundays off from all communication – no texts, no calls, no e-mail. Our communications sustained her, but her energy was often so low that they was simply too much.

Karen was always interested in the rest of us. She wanted to know who had a new grandchild, who had learned to speak French or play ping pong, who was working on the issues of the day and how. Unless she was in an absolute emergency herself, she always asked after me first, and she listened all the way to the end. On Caring Bridge, she asked people to send texts and photos and anecdotes and poems that were NOT about cancer, but about themselves and what mattered to them. She didn’t want to let the illness consume her attention altogether. Karen did the needful to prepare if she didn’t make it (living will, powers of attorney, hospice research etc.) – but she also maintained hope. “I believe in miracles. Why shouldn’t I be one of them?” she asked with a raised eyebrow and a smile.

Karen was still debating where to spend her last weeks until almost the very end, calling hospices in locations where she had close friends to compare possibilities. But in the end, she decided to stay put, and fortunately an excellent residential hospice, the Holmes Park House, was nearby in Medford, Oregon. After all of Karen’s voluntary simplicity, it amused her and everyone else that she was fated to die in a beautiful mansion! She did have the clichéd champagne tastes and beer pocketbook, as well as principles about “stuff.” Our last conversation before we were under the imminent shadow of death included strategizing about how to travel if you feel horrible and can’t control your bowels, since I knew all too much about it. Before the end, Karen did manage to squeeze in two wonderful trips: Robyn took her closer to her beloved Mount Shashta, the last mountain she ever saw, and Karen drove herself to visit her treasured friend Helen, who has dedicated her life to helping the dying and lives right by the ocean.

When she finally agreed to be admitted to hospice care (while still in her own apartment), Karen felt a huge burden lift. Her nurse became the coordinator and orchestrator that she’d been for herself all those months. She’d had so much support, research, and questions from our circle, which was a huge help but also overwhelmed her at times. Now one person was the key to her care, at least on the allopathic side. Karen still saw herself living into the fall, her favorite season other than winter, and I was trying to organize September/October visits from her close friends (including me). I’d hoped to meet her in Colorado or at least see her at home.

Sadly, her situation plummeted in mid-August. Karen went straight from an emergency room admission for severe abdominal pain to the residential hospice, where she was given one to three weeks to live. We were all shocked, including her, but her dear ones rallied round, and we were in constant contact by text and otherwise. Her hospice nurse friends came from afar, and blessed the place she had chosen. Karen was surrounded 24 hours a day at the end by people who cherished her, with Robyn in the lead. Those who couldn’t be there physically spoke with her in brief calls so she could hear our voices, even though she couldn’t respond. I read a poem about the beautiful approach of the angel of death. Joanna gave her a vision of birds taking flight.

Once Karen knew that her death was inevitable, she surrendered with grace and expediency. “I’m so glad,” she said, “that I lived long enough to know I was loved.”

When Karen met me at the hotel she’d reserved for us, she was agitated and exhausted from all the preparations, but happy to see me. I suggested a walk, since she’d thoughtfully put us right by a silvery river and a city park that was still green despite the onset of winter. Walking had always helped us before. We meandered alongside the water, watching the ducks and their antics, and admiring the lean beauty of the deciduous trees. We had a delectable local meal that night, something Karen had always enjoyed, and the next day another walk in an extensive park with huge conifers and a former filbert orchard. At times she was preoccupied, but we had many joyous moments as we wandered. “I see why you insisted that we get here in time to enjoy ourselves,” Karen admitted before we went to the hospital for pre-op. I had been through cancer with a friend before, and I knew we might never have fun again in the same way, and that she might never or almost never feel as well as she did at that moment. But I didn’t say that, of course.

When Karen met me at the hotel she’d reserved for us, she was agitated and exhausted from all the preparations, but happy to see me. I suggested a walk, since she’d thoughtfully put us right by a silvery river and a city park that was still green despite the onset of winter. Walking had always helped us before. We meandered alongside the water, watching the ducks and their antics, and admiring the lean beauty of the deciduous trees. We had a delectable local meal that night, something Karen had always enjoyed, and the next day another walk in an extensive park with huge conifers and a former filbert orchard. At times she was preoccupied, but we had many joyous moments as we wandered. “I see why you insisted that we get here in time to enjoy ourselves,” Karen admitted before we went to the hospital for pre-op. I had been through cancer with a friend before, and I knew we might never have fun again in the same way, and that she might never or almost never feel as well as she did at that moment. But I didn’t say that, of course. Joanna and I went out to visit Karen for a week in late February, while she was going through chemotherapy. Despite her weakness and digestive issues, we managed to travel to see the majesty of Mount Shashta, a looming presence encased in snow just across the California border. The three of us stood in awe on a bright winter day. Even 25 miles away, we felt the presence, and Karen was in her element. A few days later, she took us out for an extravagant and scrumptious dinner in an historic inn in nearby Jacksonville. We ate by firelight in a cozy room with rustic stone walls. Karen had even chosen the specific, secluded table. Although she threw up later, she thoroughly savored her lamb chops and potatoes Anna. Some pleasures are worth it. At her home, I cooked gallons of bland soup and bone broth and froze it, and Joanna hung curtains, fixed electrical issues and created calm.

Joanna and I went out to visit Karen for a week in late February, while she was going through chemotherapy. Despite her weakness and digestive issues, we managed to travel to see the majesty of Mount Shashta, a looming presence encased in snow just across the California border. The three of us stood in awe on a bright winter day. Even 25 miles away, we felt the presence, and Karen was in her element. A few days later, she took us out for an extravagant and scrumptious dinner in an historic inn in nearby Jacksonville. We ate by firelight in a cozy room with rustic stone walls. Karen had even chosen the specific, secluded table. Although she threw up later, she thoroughly savored her lamb chops and potatoes Anna. Some pleasures are worth it. At her home, I cooked gallons of bland soup and bone broth and froze it, and Joanna hung curtains, fixed electrical issues and created calm.