It chilled me to the bone when I heard Joel Rose on Morning Edition (June 27) report on his visit with other press reporters to the facility in Clint, Texas, a reaction to the appalling conditions reported by attorneys earlier in the week. When Joel reported on how clean the facility was, with shelves of snacks, all I could think of was how the Nazis hoodwinked the International Red Cross at Terezin. The IRC visit and report bolstered world confidence that things just couldn’t be that bad for the Jews in the camps, and made Hitler’s story credible.

Clint Texas Detention Center

Terezin from above

The Border Patrol invited the press to Clint because of the horror stories that emerged when attorneys interviewed some of the more than 250 children in the facility. They reported appalling conditions, then demanded court relief: unsupervised children living in filth, hunger, no basic sanitary materials, sleeping on the floor. A government attorney, Sarah Fabian, had earlier argued that beds, soap and toothbrushes were not necessary to provide safe and sanitary conditions for migrant children, which are required under an earlier court order.

Even after its director resigned, the Border Patrol had to fight back against all this bad publicity, and after a couple of days they opened the doors to the press—no cameras of course, and no access to the children. Before NPR host Steve Inskeep put these remarks in context, here’s what reporter Joel Rose said:

“And what I saw is really totally different from the picture painted by these lawyers. The facility was clean. They did not let us talk to the kids, but they showed us the holding cells where more than 100 children are now staying. They showed us the pantry full of snacks – microwavable burritos and soup – and the supply room, where the agents keep toothbrushes and soap and clothes. And the Border Patrol says that these lawyers who visited the site last week did not see any of this, that they only interviewed the children in another room.”

Inskeep quickly reminded us of the lawyers’ testimony about actual conditions, and Rose interviewed Clara Long of Human Rights Watch, who said “You’re going to a facility that has been prepared for a tour. They’ve also moved out . . . children from the facility before you visited. And they didn’t give you access to speak directly with children so that they could tell you what was happening and what they had been through in detention.” Here’s the full interview.

The Fox News View: Just as Grim

By the way, the Fox News reporter present on the same tour reported that:

- 117 children are there now, down from about 250 when the lawyers visited. This means that about 133 have been shipped off elsewhere. The peak, according to Fox, was 700 two months ago, in a facility designed to hold 105 adults.

Children being removed from Clint Center

- The children are eating only oatmeal for breakfast, ramen noodles for lunch, and burritos for dinner. Anyone who knows anything about nutrition can understand why they are hungry. There is no kitchen on site.

- To serve those 117 children, there were seven Port-a-Potties outside and military-style showers. The picture below is of such showers at Fort Lee. The full Fox story is here.

Military style showers at Fort Lee

Parallels with Terezin

Now let’s go back to Terezin. In that case, it took months to prepare, not just a few days. To their credit, Danish leaders insisted that they wanted to interview the Danes who were interred at Terezin. Finally, after much stalling, the German authorities agreed, and they set about preparing for the June 1943 visit. This photo shows children greeting the Red Cross:

Terezin children greeting Red Cross

Here are the similarities:

- • The camp was cleaned up and “beautified,” in this case with Jewish women sweeping up streets with hairbrushes, and planting flowers throughout. At Clint, all they had time for was cleaning. I wouldn’t have liked to be on duty those few nights.

- • 7,503 inmates were sent to Auschwitz to reduce overcrowding. In Texas, they transferred about half the kids elsewhere.

- • Special attention was given to fool the Red Cross into thinking that food supplies were adequate. A chilling testimony by survivor Eva Erben tells us that the children were told to go to a certain corner, where they would receive bread and butter and sardines, as opposed to the usual starvation fare. Then, when the camp commander came by with the Red Cross officials, they were to say “Oh, Uncle Rom, not bread and sardines again!”

Children at Terezin during Red Cross visit

Not content with this performance, the Nazis prepared a propaganda film to reinforce for the world what only a few had seen – then deported and murdered the director and cast.

What now?

The Red Cross bought it, and so did the world. Whom will we believe now– the children speaking through their lawyers, who say they are hungry, who were visibly dirty, had no beds or care or education – or the Border Patrol, who has staged this “visit” just as unscrupulously as the Nazis did at Terezin?

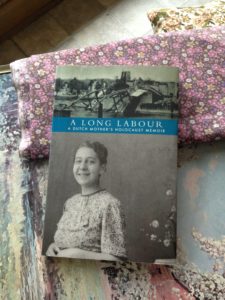

During my 13 years researching and writing

During my 13 years researching and writing