The last few days fulfilled my longtime dreams of what I might do as a writer in the world. Being with two groups in New Mexico to discuss the importance and possibility of resistance gave me a sliver of hope, even ten days before Donald Trump’s inauguration. If there are 35 people in a red state in two locations who are receptive to that message, we need not despair for our country. Around the talks, I got to visit with dear old friends, see countryside utterly different from my usual haunts, appreciate the marvels of sandhill cranes for the first time, and learn from the Pueblo Native Cultural Center in Albuquerque.

The last few days fulfilled my longtime dreams of what I might do as a writer in the world. Being with two groups in New Mexico to discuss the importance and possibility of resistance gave me a sliver of hope, even ten days before Donald Trump’s inauguration. If there are 35 people in a red state in two locations who are receptive to that message, we need not despair for our country. Around the talks, I got to visit with dear old friends, see countryside utterly different from my usual haunts, appreciate the marvels of sandhill cranes for the first time, and learn from the Pueblo Native Cultural Center in Albuquerque.

Because of my astronomer partner, I knew I was going to be in Socorro, New Mexico, and tried to think about who might be interested in a book talk about An Address in Amsterdam, my historical novel about a young Jewish woman who joins the anti-Nazi underground. With a little research, I tracked down a small Unitarian congregation which was willing to take a chance on a talk called “Resistance Then and Now.” Richard Sonnenfeld, the kind man who’d said yes and done the promotion, welcomed me to the sunny social hall of the local Episcopal church where the UUs meet on Sunday afternoons. We chatted about the latest outrages on the news as we arranged chairs. My partner had invited some astronomers to join us, and all in all about twenty of us collected.

Warm welcome from Richard Sonnenfeld

After an organ prelude – unique in my decades of speaking to groups – I began the conversation by talking about the way the Dutch faced the choices of collusion, collaboration and resistance. There were so many ways to resist, from the low key ones like reading an underground newspaper, to the much riskier endeavors of delivering such papers (as my book’s heroine does) or hosting Jewish families or others who needed to hide. When we began the discussion, we talked about the possibilities for resistance now in a number of contexts: finding and sharing information that is increasingly unavailable, standing beside or sheltering persecuted people, and protesting or taking other direct action. It was impressive to hear the number of local initiatives which had already begun. To that list we added the intention to reach out to the local mosque and find out what support they might welcome. I felt cheered by the time we parted company.

Driving from Socorro to Albuquerque a few days later meant huge vistas rimmed by mountains, and desert vegetation broken by occasional settlements. Thanks to the wonders of GPS, I navigated smoothly through the city streets of a place I’ve never been. Instead of a stuffy, set-apart museum building, I found a handsome Art Deco storefront that drew people in just like a store, with a sandwich board on the pavement and interesting stuff in the windows. Variegated turquoise tiles across the whole façade livened the whole place up, with a bright sign across the full width for the “Holocaust and Intolerance Museum of New Mexico.”

After greeting the staff and volunteers who keep the place alive, I passed uneasily under the replica of the gate into Auschwitz: Freedom through Work. To my left were a series of exhibits about the Holocaust, mostly presenting material that was familiar to me in a way that was easy to access, with lots of pictures as well as text. On the other side were hard-hitting exhibits about hatred and where it can lead – the Orlando shootings, the Armenian genocide, the Rwandan genocide, and how propaganda works to manipulate our perceptions. I was saddened to hear that the Museum lost funding from a major Jewish organization because of the broader topics they cover. To honor the Holocaust of the Jews and to recognize its hideous uniqueness is not, in my view, to say that no other genocides count.

Like any book lover, I soon went downstairs to the library and study center where I eventually gave my talk. The collection was as comprehensive as the exhibits. I was delighted to find my bible for my own book, Jacob Presser’s Ashes in the Wind: The Destruction of Dutch Jewry, like finding an old friend among strangers.

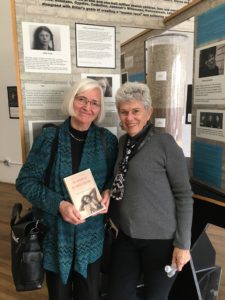

Board Chair Jennie Negin & Mary

The Museum kindly arranged for a delicious cold cuts luncheon on proper rye bread, and soon we had a dozen people munching and chatting. By the time we went downstairs, about fifteen people had gathered, thanks in part to Board Chair Jennie Negin’s decision to close the Museum for an hour so all the volunteers could attend. I felt honored to be among them: a couple of high school students, an historian, a retired opthamologist, a supporter of the Southern Poverty Law Center, an African American woman married for decades to a Jewish man, her mother, a capable librarian and others, all drawn there to support the Museum’s work. I talked with them about my own background, what drew me to the story of the Holocaust and Resistance in the Netherlands, and gave them some highlights of what I’ve learned and how it applies to us all now.

Questions and comments poured in, including a painful one about the role of Jewish people who collaborated in some way. We talked about the Jewish Council and its very ambiguous role in representing the Nazi demands to the community, and negotiating on its behalf but often futilely. We heard about the dollhouse in the Museum collection, which was hidden in a neighbor’s attic and survived the war, unlike its original owner. One man honored me by saying he would place me among the righteous Gentiles. This gesture feels like an anointment – and a charge to continue to get this message out into the world. Not just the memory, as important as that is, but the message of the courage of the resistance and how necessary it is now.