Flashes of silver announce the presence of the Holocaust Names Monument, fought over for years but finally opened in September 2021 thanks to the Netherlands’ highest court (once headed by Mr. L. Visser, whose colleagues voted to comply with the Nazi order to fire him because he was Jewish).

As we approach, a young couple stands in front of it, embracing. At first I think one is comforting the other, but they are simply in love and oblivious. No harm in that. We cross the busy street and entered the sharp corners of the brick walls, where 102,000 names are inscribed, each on their own individual brick with their birthdate and age when they were mass murdered.

The bricks’ colors are in a range of sandy and ruddy shades, but uniform in size whether they are for an infant or an octogenarian, a famous person or someone who was unknown except to family and friends. Once we enter the world that monument makes – “backward” at the letter Z, but it didn’t matter – it captures us completely. A wall of 1,000 blank bricks follows the Z listings, to allow for newly discovered victims, and those who remain unknown.

The bricks’ colors are in a range of sandy and ruddy shades, but uniform in size whether they are for an infant or an octogenarian, a famous person or someone who was unknown except to family and friends. Once we enter the world that monument makes – “backward” at the letter Z, but it didn’t matter – it captures us completely. A wall of 1,000 blank bricks follows the Z listings, to allow for newly discovered victims, and those who remain unknown.

The walls are taller than we are, with the mirrors overhead bringing in the world of today, the modern building across the street, the trees which are the only adornment among the walls.

The traffic noise fades but is still prominent. Joanna and I drift in different directions. At first, the sheer numbers overpower me: where will it end? the walls seem to go on forever. A young tree’s branches spread like an opening hand among the bricks. Could I read the names one by one during this two-week visit? Only if I did almost nothing else. Patterns begin to appear: so many young people! The youngest I see is eight months old, but there are many, many adults in their twenties and thirties. Some names appear four or even five times with different ages, the intention of continuity in a family now torn like paper. And some families must have lost everyone, or almost everyone.

Is it my imagination, or are the reflections in the mirrors distorted? The visions of everyday life overhead seem a bit swirly, but at one point, I look straight up, and see myself and the names crystal clear, together. From reading, I know that the mirrors seen from above spell out in Hebrew letters “In memory of”. No embellishment or editorializing, simply that.

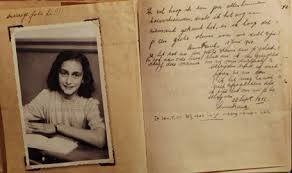

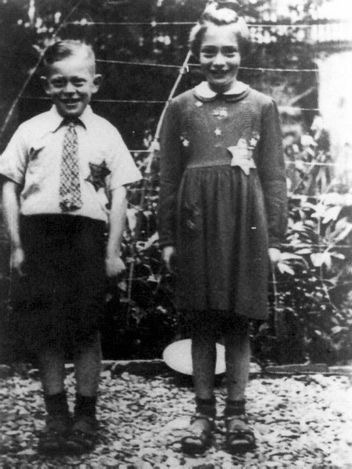

Among the tens of thousands, it’s irresistible to look for specific people who are as real to me as anyone I’ve ever met. I find Miss Henriette Pimental first, the heroine who oversaw the saving of hundreds of children right under the nose of the Nazis, just a few blocks from the Monument. Nearby are the Pais sister and brother whose photograph haunts me: they have the broad, appealing smiles of a nine and eight year old, wearing their Nazi-inflicted stars. Survivor Rudi Nussbaum had finally persuaded his parents to go into hiding, and arrived at their apartment to relocate them, only to find that they had just been deported the night before. I look for their names, but there are too many Nussbaums of about the right age for me to figure it out without their first names. This too brings the reality home. Too many means too few.

Bringing the search into the present moment, I wonder about the M. Pels whose house we are staying in, the man whose business was partly ice cream. There’s a restored business sign on the front of the building. Bricks cite Marcus, Moritz or Maurits (yes, two spellings). Is one of these our predecessor? Or is he still alive somewhere, or comfortably buried in an actual grave, unlike 80% of Amsterdam’s Jewish population?

The line of white rocks at the foot of the brick walls have a pure quality because they are all such a stark color in contrast to the bricks themselves. The shapes vary, however, unlike the bricks. Not only do they have symbolic meaning as recognition of the dead, but they are also a relief to the eye in that place of straight lines and sharp angles. Every time I go around a corner with its hard acute angles, I wince. Joanna is talking with a younger woman who is dressed all in black. We meet both her and her mother, who is my age; they come from the northern city of Groningen, and are engaged in creating an historical walk that will cover some of this history, but do so by walking and settling in a café and learning what can be seen from that place. It will “go live” May 4/5, the times of remembering and liberation, too late for me on this trip but not, heaven willing, the next. Joanna tells them all about my book. We smile and laugh together at the serendipity of our meeting. “The ghosts are at work,” I say, gesturing at the walls. Everyone nods and smiles, but nobody laughs. I think it would please them to hear laughter, and the pale pink flowers on the nearby tree would delight them. Only in one place have flowers been left. Tomorrow I can change that.

The Holocaust Names Monument has already started its work on me, in part because the site is caught between two worlds. On one side is the constant roar of vehicle traffic, the lanes of bicycles with their insistent bells, and the chats and giggles of pedestrians. On the other is a garden with carpets of purple and white crocus gathered at the feet of trees. One pale pink prunus peeks over the edge of the Memorial’s walls. The garden can be entered directly; a sign welcomes you to bring a picnic. On the other side stands the 1681 Amstelhof, once a retirement home for elderly women, now the Hermitage. Six years earlier, the Sephardic Jews had already erected their magnificent nearby Portuguese Synagogue. Amsterdam was a land of unique opportunity for them. No one could have imagined how much the Jewish population would expand in the coming years, nor that 80% of them would be rounded up and murdered. It still seems inconceivable. While I’m here, I plan to visit every day, and see what can be learned there. I’ll keep you posted.