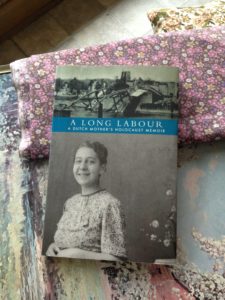

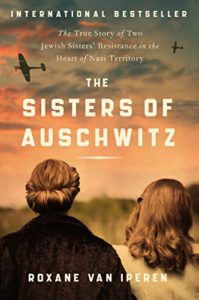

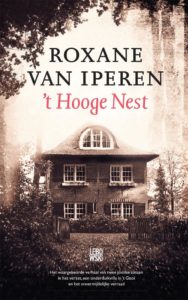

When I learned about “The Sisters of Auschwitz” by Roxane van Iperen, I was excited to discover that it was really about Amsterdam’s Brilleslijper sisters and the remarkable colony of artists and resisters they established. The sisters were real Jewish women in the resistance, a little older than the fictional heroine of An Address in Amsterdam but very much in the same predicament. And the author engaged with their story in an unusual way. She discovered hidden doorways under the carpet of her home as it was renovated, and came upon resistance newspapers and Yiddish sheet music. The book was immensely popular in the Netherlands, staying in the top ten nonfiction sales for weeks as “The High Nest.”

When the text was translated this year, it was renamed “The Sisters of Auschwitz”. That led me to think that it would be a gut-wrenching story set in a concentration camp, and the latter part of the book is set there. Like so many other memoirs and histories, it includes remarkable stories of defiance (like singing Yiddish songs and the Marseillaise even in the face of the gas chambers) and demonstrates the essential role of human connection. “If they do not look after each other, everything is finished.” How many learned that lesson in the hardest possible way! We cannot have too many such stories. At the same time, for me the most priceless part of the book was its depiction of these two young women starting their families, and taking huge risks for the resistance.

Printing for the Resistance and Nursing at the Same Time

The vision of one of them printing an underground newspaper with a baby on her hip and a toddler nearby is unforgettable. van Iperen writes in the present tense, giving her words the immediacy and breathlessness of this time. She paints the scene so convincingly. It took me right back to the events depicted in my own book, like the speech in which Prof. Cleveringa denounces the Nazis for firing his mentor, the Jewish authority Dr. Meijers, and the students rise up and sing the national anthem.

Janny Brilleslijper

That unforgettable speech was followed some months later by the first roundup on a frigid February day, and the only general strike in Western Europe to protest it. “The Sisters of Auschwitz” emphasizes the role of the communists in organizing the Strike, and the fact that their role is often suppressed or overlooked. The book captures the darkening of the light, not only for the country and the city, but for the individuals. It traces the Jewish community’s journey from gullibility to believing the worst.

The author owns up to the big scandal of this time: the Belgians rounded up 30% of Jewish people, the French 25%, and the Dutch 76%. She also is willing to say out loud that, after a certain point, many non-Jews simply gave up, and became “traitors without a uniform.” At the same time, many did resist, but they had less “skin in the game” than their Jewish counterparts. In addition to the inspiration of seeing young mothers defy the Nazis, we get to witness something even more remarkable.

The High Nest: A Center of Art, Music and Resistance

In February 1943, they managed to rent The High Nest (where van Iperen later lived), an isolated spot just outside Naarden, not far from Amsterdam. They continued to make music and art, producing their own performances of major operas as well as the Yiddish songs which are Lien’s profession. It’s a place where all kinds of endangered people are welcome, which is ultimately part of their undoing. And it’s a place where toddlers and young children can play outside from dawn to dusk if they wish.

Lien Brilleslijper

Finally, The High Nest provides a hearth to which the adults can return after doing their resistance work elsewhere. This is that rare, rare Holocaust story which does have a happy ending, at least in part. I won’t spoil it for you, but I do heartily recommend the book. It’s a real contribution to the literature of this time. My very best wishes to all of you who feel, as I do, that books are life. Right now they are more central than ever, especially as we go into the winter. This one will remind you of the actions and values that brought people through even harder times than these.

During my 13 years researching and writing

During my 13 years researching and writing

The last few days fulfilled my longtime dreams of what I might do as a writer in the world. Being with two groups in New Mexico to discuss the importance and possibility of resistance gave me a sliver of hope, even ten days before Donald Trump’s inauguration. If there are 35 people in a red state in two locations who are receptive to that message, we need not despair for our country. Around the talks, I got to visit with dear old friends, see countryside utterly different from my usual haunts, appreciate the marvels of sandhill cranes for the first time, and learn from the Pueblo Native Cultural Center in Albuquerque.

The last few days fulfilled my longtime dreams of what I might do as a writer in the world. Being with two groups in New Mexico to discuss the importance and possibility of resistance gave me a sliver of hope, even ten days before Donald Trump’s inauguration. If there are 35 people in a red state in two locations who are receptive to that message, we need not despair for our country. Around the talks, I got to visit with dear old friends, see countryside utterly different from my usual haunts, appreciate the marvels of sandhill cranes for the first time, and learn from the Pueblo Native Cultural Center in Albuquerque.