“Nach Holland: The 1940 Invasion of the Netherlands through German Eyes” at Amsterdam’s Resistance Museum is a completely new take on the unexpected invasion of the Netherlands. Interestingly, ten percent of Germans had a camera in 1939, and many who invaded the Netherlands brought them along. The exhibit shows 150 of their photos, a collage of images that range from the delightfully ironic to the somber.

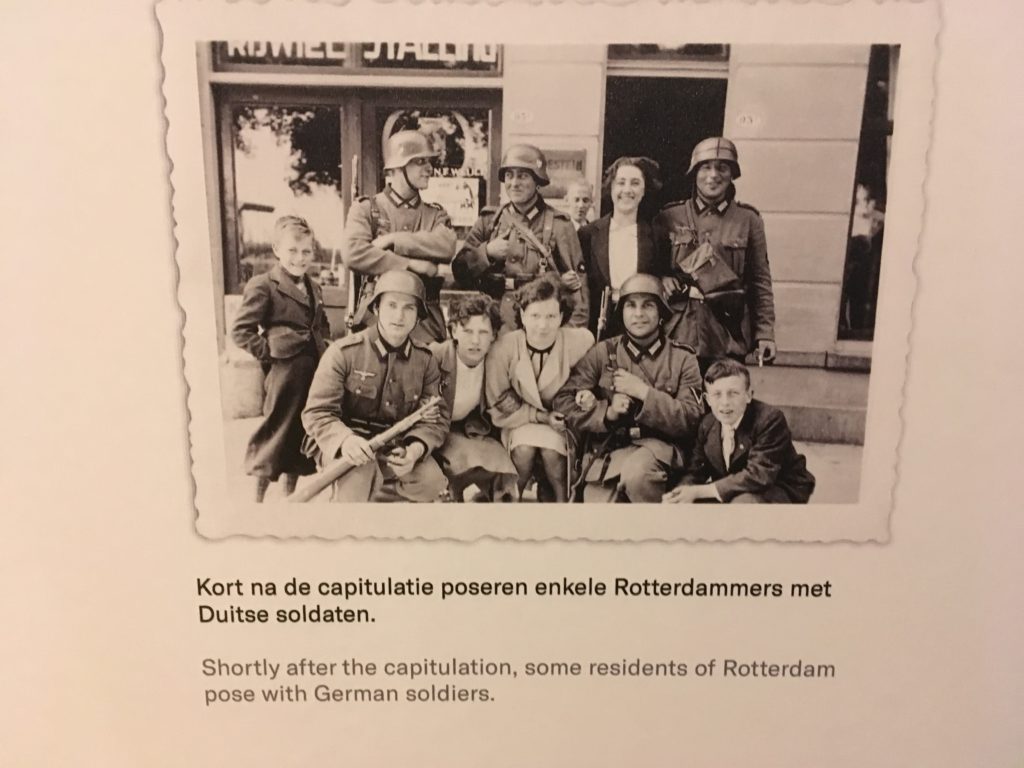

At first, the tone is a kind of lark for boy scouts. The Germans are smiling, things are going swimmingly, and some of the Dutch populace is seen as welcoming their new neighbors. There are even photos of German and Dutch soldiers together. But a different and mixed picture soon emerges. We see pictures of Dutch POWs forced to bury German casualties, or men cowering in trenches. A stream of civilians fleeing their homes clarifies the stakes.

It begins to look like a real war. One small bit of comedy is that the Germans handily captured the Rotterdam airport, only to discover that the earth there was too mucky to hold up their heavily laden aircraft, so they ended up landing on the nearby beach.

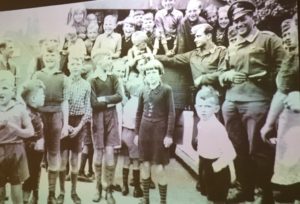

With foreknowledge, it was poignant to see photos of the children of Arnhem gathered as the Germans arrived, with one soldier smiling broadly. How many of those kids would survive one of the bloodiest battles of the war, “the bridge too far” which left 17,000 troops and an uncounted number of civilians dead?

With foreknowledge, it was poignant to see photos of the children of Arnhem gathered as the Germans arrived, with one soldier smiling broadly. How many of those kids would survive one of the bloodiest battles of the war, “the bridge too far” which left 17,000 troops and an uncounted number of civilians dead?

In some areas, the Dutch retreated quickly, but in others they fought very hard and held their ground. Among the most impressive of these achievements was holding the Afsluitdijk, a 20 mile long dam and causeway which was built to divide the North Sea and the Ijsselmeer – not in our time, but in the 1920s and early 30s. Ironically, the soldiers who had successfully defended it had to hand it over to the Germans at the time of the overall capitulation. It must have been a bitter pill.

Overall, it only took a few days for the armed struggle for the Netherlands to be over, from the first attacks on May 10, 1940, until the capitulation on May 14. A sad fact is that the Germans said they would allow the Dutch up to a certain time to accept or reject an ultimatum. If it was rejected, they would bomb the city of Rotterdam. When the Dutch received the physical document, it was not properly signed, and was sent back. By the time it was returned with a signature, the bombers were on the way – two and a half hours before the ultimatum was supposed to expire. In only 15 minutes, 25,479 houses were reduced to rubble; 78,700 were homeless; and 850 civilians were dead. And yet, after all that, a photo was taken with civilians and Germans together.

“Now it begins,” I couldn’t help thinking, as I saw the photograph of the Germans entering Amsterdam. How fortunate that no one alive then could foresee exactly how terrible the next five years would be – worst for the 80% of Jewish people who were rounded up and murdered, and unimaginably hard for everyone else.

Every time I approach the Verzetsmuseum, I am carried back to my early visits there in 2001. A friend used to say, “You went in one door and came out another.” While my obsession with the Holocaust and Resistance here has many sources, a crucial experience was realizing that 1940-45 wasn’t just a steamroller. There were so many small actions both by the Nazis and by their opponents, and there was a dignity in resistance – even at its most “insignificant” – that I had never understood before. I think of the woman who knitted together the fingers in the gloves she was forced to make for the German soldiers. Walking through the Museum on my way to the temporary exhibit of German invaders’ photos that was my goal, I remembered so much. Watching a film with my beloved Eliane Vogel Polsky, who was hidden in plain sight as a teenager, about a family with their happy children the night before deportation. She couldn’t stand it, even though she’d tolerated so much else: “We don’t have to see that.” Hearing the sound of the underground presses and seeing the machines that were put together, then taken apart, which I’ve talked about so many times since to various audiences.

Listening to the recording of a woman responding to a request to hide in her house with a closed door: “We don’t have room,” and its variations. Learning about the 1944-45 Hunger Winter, and my complete shock that Amsterdam lost more than 2,000 people to starvation. As is so often the case here, I felt as though I was walking over my own footsteps since 2001, a kind of archeology of my slowly growing understanding of this place and time, and how it relates all too vividly to our own.